On behalf of everyone concerned about housing affordability, thanks to Prime Minister Tony Abbott and Treasurer Joe Hockey for putting the issue on the front pages of the media for the past two weeks.

In case you missed it, the discussion got started when three of Australia’s highest-ranking financial regulators – from ASIC, the Reserve Bank and the Treasury – each in short succession warned about the financial risks of the inflated property market in Sydney and Melbourne, with the Treasury Secretary calling Sydney ‘a housing price bubble… unequivocally’.

Asked in Parliament if he agreed with the Secretary, Prime Minister Abbott replied:

As someone who, along with a bank, owns a house in Sydney, I do hope that our housing prices are increasing. I do want housing to be affordable, but nevertheless I also want house prices to be modestly increasing.

The next day the Treasurer made the same point, telling Parliament that ‘I think we should be welcoming an increase in housing values’, but then went further, telling the media that would-be buyers should ‘get a good job’ and that housing in Sydney was not unaffordable, on the basis that some people were buying it.

The response has been an extraordinary extended discussion of Australia’s housing affordability problem, ranging from the experiences of would-be home buyers who are priced out, the property interests of the Treasurer and other MPs, reflections on the politics of property markets, the ‘social harm’ of widening housing inequality, why high house prices are bad for business, why you don’t just need to get a good job but also good parents, where an essential worker can and cannot afford to buy, the growing deposit gap, and whether cracks are appearing in current policy settings.

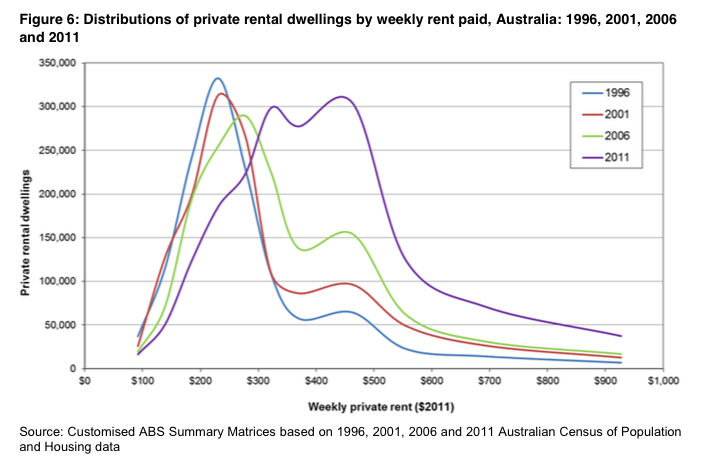

If anything has been missed in the discussion, it is the problem of rental affordability, which is where the greatest hardship occurs. If you can find just a little room in your own discussion of housing affordability for the rental problem, fill it with this chart (from AHURI research by Judy Yates, Kath Hulse, Maggie Reynolds and Wendy Stone) which shows the changing shape of the Australian rental market.

The purple line (2011) is the closest measure we’ve got to today’s market. It shows both the absolute growth in the number of rental properties (the area defined by the purple line – compare it to that of the blue line from 1996), and the shift in the market away from the low cost end to the higher up the scale of rents. Look at that pile of properties renting in 1996 for a bit more than $200 per week; in 2011, the bulk of the market is around $400 per week. Note that the rent scale is in $2011, having adjusted previous years’ data for inflation: what’s depicted is the shift in real rents throughout the market, and it is doing real damage to low-income households.

The situation for these households is even worse than the chart suggests because, as the research points out, not only has the number of low-cost rental properties declined, most are occupied by households who could actually afford to rent higher up the scale (you cannot blame them – they’re probably would-be home buyers, saving up).

As a result, about 80 per cent of very-low income households (that is, in the lowest 20 per cent of households by income) living in private rental are renting unaffordably (that is, paying more than 30 per cent of their income in rent). In fact, a quarter of these households pay more than 50 per cent of their income in rent. Amongst low-income households (that is, the next rung up: 21-40 per cent of households by income), about one third are renting unaffordably. The majority of these households include children.

And as for what renting unaffordably really means, consider this AHURI research by Terry Burke and City Futures’ Simon Pinnegar. Their survey of low-income households renting unaffordably found:

- 35 per cent say that their ‘children have had to go without adequate health and/or dental care’

- 32 per cent ‘sold or pawned personal possessions’

- 28 per cent ‘approached a welfare/community/counselling agency for assistance’.

Many of these households will have given up on the idea of owning a house, but what they have in common with frustrated buyers is that they can point to the same cause of their different problems: the rampant speculation in housing in Australia.

Housing speculation bids up purchases prices, as would-be buyers know all too well; but it also drives the changing shape of the rental market. The tax settings that encourage speculation – the capital gains tax exemption for owner-occupied housing, negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount for rental housing – deliver the greatest tax advantage to persons with the highest incomes and the highest levels of gearing, pursuing capital gains rather than rental income. The practical result is a preference for high-value (and hence high rent) properties in established areas, such that when low-value, low-rent properties come onto the market, speculators are less likely to buy them, and they drop out of the rental market – and those remaining in the rental market become scarcer, and less cheap.

Our pro-speculation tax settings do not make renting any less expensive; on the contrary, they make rental affordability worse.

The housing affordability discussion of the last couple of weeks has emboldened calls to change our tax settings to reduce the encouragement to speculate. We should do this not only to help frustrated would-be owner-occupiers, but also the hundreds of thousands of renters stressed by the distorted shape of the rental market.

Another response to all the attention on housing: a new political party! http://news.domain.com.au/domain/real-estate-news/house-price-debate-gives-rise-to-the-the-affordable-housing-party-20150615-ghoaqk.html

NSW community sector housing peak organisations on the housing affordability discussion: http://intranet.tenants.org.au/print/150610finaljointstatement.pdf