By Bill Randolph, Director, City Futures Research Centre. Originally published in the Sydney Morning Herald.

Gough Whitlam once wrote that “a citizen’s real standard of living, his children’s opportunities for education and self-improvement …are determined not by his income, not by the hours he works, but by where he lives.” In the 40 years that have passed since Gough Whitlam penned those words, far from improving, geographic inequality in Australia is getting worse. Nowhere is this more evident than in the suburbs of our major cities.

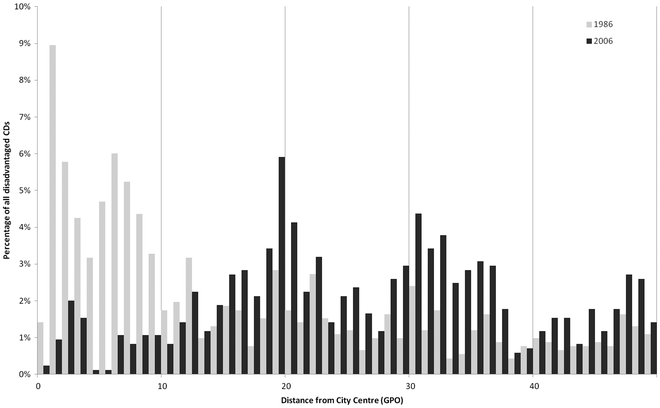

Research by the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW shows that since 1986 across our five largest capital cities, the proportion of people classed as highly disadvantaged in suburbs 10 kilometres or further from our city centres has jumped by at least 100 per cent. In Sydney for example, the rise in disadvantage in the band 10 to 19 kilometres from the CBD is 80 per cent, rising further to 139 per cent in the 20 to 29 kilometres band. By contrast, the rate of disadvantage within 10 kilometres of inner Sydney has shrunk by 82 per cent.

(Disadvantaged Census collector districts (CDs) in Sydney, distance from city centre, 1986 and 2006, from Randolph and Tice (2014) ‘Suburbanising Disadvantage in Australian Cities: sociospatial change in an era of neo-liberalism’, Journal of Urban Affairs vol 36 no 1.)

A fortnight ago, the ABS found that more than half a million low income households renting privately in Australia are suffering housing stress (paying more than 30 per cent of their income in rent). No wonder a third of low income households surveyed recently by City Futures and the Australian Housing Urban Research Institute said their children had to go without adequate health and dental care, another third sold or pawned personal possessions and 28 per cent had approached an agency for help. It is an uncomfortable fact that child poverty is on the rise.

Prime Minister MalcolmTurnbull assured us moments after taking the reins that there had never been a more exciting time to be an Australian. Almost in the same breath, he celebrated the importance of our cities, because “that is where most Australians live, and it is where the bulk of our economic growth can be found”.

In this, Turnbull is absolutely correct. Our cities are the economic powerhouses responsible for 85 per cent of our national wealth. However, in Australia, Britain and the US, there is a growing gap between those who are enjoying the wealth and opportunities and those who are being left behind.

Here in Australia, the backdrop to these changes lies in the shift to the policies of economic rationalism and the on-going neo-liberal ascendancy that emerged in the 1980s, a decade that represents a watershed in post-war Australian life. Since then, we have seen two distinct phenomena emerge. Firstly, a stretching of the wealth continuum towards those on the highest incomes. And secondly, the great urban inversion of our cities. The once-reviled inner cities are now the centres of our greatest wealth and productivity, and the homes that immediately surround them among the most expensive in the world.

Once dotted by industrial and manufacturing hubs, the middle and outer ring suburbs of our cities were a place where the average worker could work, support a family and buy a home on an average wage. With the relocation of many of these jobs offshore, a new set of challenges is faced by many Australian families. Unemployment, job insecurity, long commutes to available jobs, poor health outcomes, high house prices and rental stress are just the beginning.

This changing geography has great implications for policy makers and I welcome the NSW government’s decision to introduce the Greater Sydney Commission, which it is hoped will finally eliminate the fragmented decision-making that has dominated Sydney for far too long.

Addressing the growing suburbanisation of disadvantage would be a good starting point for the new commission and thoughtful densification must be part of that equation. That doesn’t mean throwing up 20-storey towers full of one and two bedroom units alongside every rail station. Tall towers might be a starting place for singles and young couples but they aren’t the best place for growing families or couples wanting to downsize. Neither are they particularly affordable.

Someone once said that without good urban data, you are blind and deaf and in the middle of a freeway. And it is here that universities have a role to play. We stand perfectly poised to work with governments, policy-makers and city builders to provide the hard data, the research and the facts from which all good decision-making flows.

If policy makers, including our latest Prime Minister, are to get serious about making our cities better places to live for everyone, working from the facts would be a great place to start.

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.