One week on and the election has produced a government – which, for a while there, didn’t look like a sure thing. However, the more remarkable result of the election campaign was this: one of the major parties campaigned on reforming tax settings to reduce house price speculation and, having grasped what was long supposed to be the third rail of Australian politics, it didn’t die – on the contrary, they got votes.

Labor gained in the face of the property lobby in rampant scaremongering mode: notably the Property Council’s ‘house of cards’ campaign (which combined scaremongering with some unguarded admissions) and the old ‘rents will skyrocket’ theme pushed by the Real Estate Institute. Your correspondent subjects himself (for research purposes) to a lot of property industry communications: election campaign messages included one leading property guru telling her seminar audience flat out ‘for heaven’s sake, vote Liberal’, while another property sage intoned in his newsletter that ‘Labor can suck a fart…. Sorry, property investors and the Labor Party don’t mix’. Last week The Australian reported that the property lobby was calling the campaign a success, with the Property Council observing ‘there is a correlation between electorates with high numbers of investment property owners and a lower than average swing against the government.’

Assuming that’s correct, the property lobby is badly missing the point: if ‘investors’ swung less to Labor, it means the rest of the people swung to them more.

The last time housing played anything like such a prominent part in an election campaign was 2007, when Kevin Rudd proposed to address the affordable housing crisis with tax-preferred home saver accounts, a National Rental Affordability Scheme, and making Commonwealth land available for sale or use in affordable housing schemes – but not tax reform. As it happened, one year after Rudd Labor came to office the GFC hit and, to keep credit and spending going, the Government turned again to house price speculation, stoked with big first home buyer grants – which has proved to be a more enduring legacy than its other housing policies. Housing also had a central, if uncredited, role in the 2004 election, when John Howard campaigned on ‘keeping interest rates low’ – households having just taken on an unprecedented level of housing-related debt, induced by the Howard Government’s capital gain tax discount (introduced 1999), and first home buyer grants (introduced 2000, doubled in 2001).

So what is it about things now that has put housing on the agenda in such a different way? In the last couple of years, our housing system has passed a few psychologically important thresholds: the $1 million median house price in Sydney; more than 50 per cent of home lending going to investors. Interest rates are at record lows, which ought to please people who borrowed under Howard, or Rudd – but it is not enough.

Just how the affordability problem is currently biting would-be owner-occupiers is shown in a recent report by the Australian Institute for Progress on the ‘deposit gap’ – that is, the change over time in the amount of savings required for a deposit for a home loan. The AIP, a conservative outfit with links to the Liberal Party, apparently intended its paper to contribute to the campaign against negative gearing reform – but the pictures tell a different story.

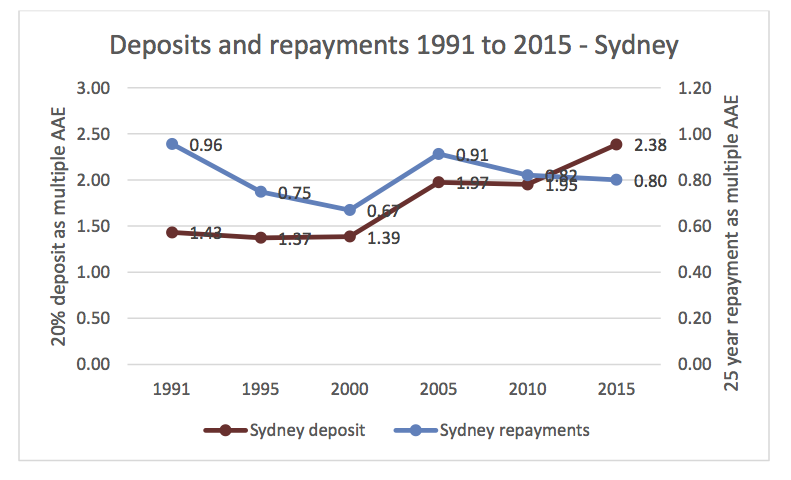

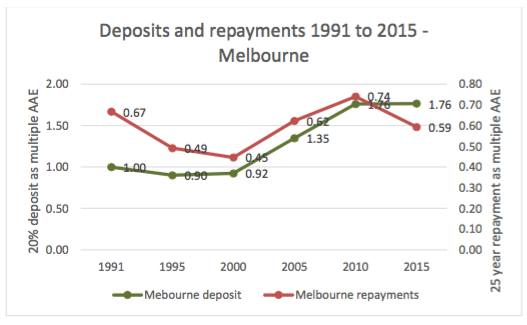

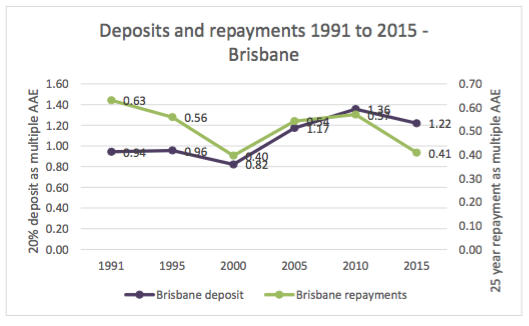

The AIP has graphed the change in the size of the deposit, relative to average earnings, required for a typical home loan, along with the change in typical loan repayments (again, relative to average earnings). The latter has gone down with lower interest rates; the former up with higher prices.

The AIP calculates that ‘Sydney repayments over 25 years are almost 16% more affordable than they were 25 years before, but the deposit is 67% less affordable. If you saved 10% of your after tax income in Sydney each year it would take you 23.8 years to accumulate a 20% deposit.’

In the other capital cities it’s a similar pattern, with lower multiples. In Melbourne, the AIP calculates that would take almost 18 years to save the deposit.

In Brisbane, it’s over 12 years.

Having put its finger on an important aspect of our housing affordability problem, the AIP badly misprescribes the treatment, recommending government-funded deposit grants, using superannuation savings for deposits, and more lending by banks and ‘the bank of mum of dad’. All of which are just more ways of getting first-time owner-occupiers paying more for housing – while those already wealthy in housing still hold the upper hand, because their deposits come from tax-exempt or half-taxed incomes – that is, capital increases from the houses (owner-occupied or rental, respectively) they already own – and because their repayments come from pre-tax incomes, giving them a cashflow advantage – thanks to negative gearing.

Greater affordability comes from being able to pay less, not more, for housing. From it too comes the prospect of better uses for money – and better applications of creditworthiness and promises to repay – in the creation of valuable new goods and services, rather than in merely punting on property. And it looks like more of the electorate is voting for it.

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.