By Chris Martin, City Futures Research Centre. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The National Cabinet announced a moratorium on evictions just over a week ago in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As government ministers and commentators have tried to make clear, it’s intended only to stop evictions – not rent payments. But the sudden losses of jobs and incomes mean many households cannot continue to pay pre-crisis rents.

Tenants are seeking rent reductions or waivers from their landlords, with disturbingly mixed results. It is time for governments to step in and resolve the issue, by legally mandating rent reductions across the board.

Read more: Why housing evictions must be suspended to defend us against coronavirus

Recent analysis of renter and landlord household finances clearly shows the latter group are much better placed to take a financial hit from this pandemic.

Up to now the prime minister has encouraged tenants and landlords to make individual arrangements. In the absence of any government guidance, agents’ and tenants’ representatives agree on this much: the situation is a mess.

Some landlords and agents are responding sympathetically. Others are hesitant, apparently wary voluntary reductions may void their insurance. Some are insisting on full payment, or even increasing rents. And some were advising tenants to draw on their superannuation to pay rent – until ASIC warned them off.

Why should government step in?

Yesterday the National Cabinet addressed commercial tenancies, but again left aside residential tenancies. It is within the power of state and territory governments to sort this mess out. They could legislate to reduce rents to some fraction of current rents or to zero – a complete suspension of rent liabilities for the declared duration of the pandemic.

With federal government co-operation, mortgage interest could receive the same treatment: mandatorily reduced or suspended for the pandemic, with principal repayments deferred.

This is the appropriate response to the peculiar nature of this crisis. The key point here is that government is deliberately suppressing economic activity to prevent transmission of the virus. With household incomes much reduced – and governments trying to top them up with new payments – it makes sense also to reduce household outflows.

A look at renter and landlord finances

The biggest household expenses to reduce are rent and interest. Here’s a quick sketch of incomes and outflows in the Australian private rental sector, using the latest available figures from the ABS, the ATO, the Productivity Commission and detailed analysis of previous rounds of data last year by Kath Hulse, Margaret Reynolds and me.

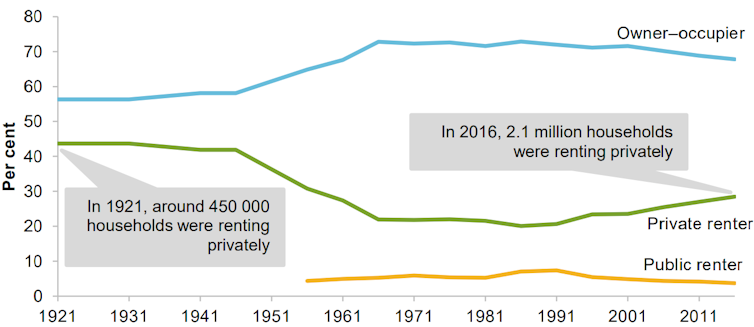

About 2.5 million Australian households rent privately. Just over half are in the bottom 40% of households by income. About one-third are low-income households paying more than 30% of their income in rent – and that’s before the COVID-19 income losses.

Read more: Why coronavirus impacts are devastating for international students in private rental housing

Private renters pay about A$43 billion a year in rent to another, smaller group of households: Australia’s 1.3 million landlord households.

A little more than half of that rental income, A$22 billion, flows right out again to banks, as interest payments on investment loans. For 60% of landlords the interest outflow, plus other property-related expenses, is greater than their rental income: they are negatively geared. For them, rental income is not about putting food on the table; it is part-funding their investment or speculation in property.

This negatively geared group receives high incomes from work and other sources. Leaving aside their net rental losses, they have an average annual taxable income of about A$94,000, versus A$54,000 for non-landlords. Landlords’ other incomes may have taken a COVID-19 hit, but the most common occupations for this group – general managers, registered nurses and accountants – have probably fared better than the casual and gig workers.

Read more: Coronavirus puts casual workers at risk of homelessness unless they get more support

Landlords who derive a net positive rental income mostly receive other income too. Their average annual taxable income is A$66,000 before net rent is added.

A relative few landlords, 16%, are post-retirement age. They may well rely on rental income for consumption, but, on average, they are rich, with almost A$3 million in net wealth.

A final point about landlords: they are more likely to have a partner than non-landlords. Presumably, then, they have access to shared resources when times are tough. The average disposable household income for landlords is A$135,000 a year, versus A$82,000 for non-landlords.

So, were tenants’ rental outflows reduced, landlord households are relatively well-positioned to bear a reduction in their rental incomes.

How to ease the burden on landlords

Landlords would, of course, also want to reduce their own outflows. They have probably already done so, because the pandemic has closed so many discretionary spending opportunities.

Another outflow – the A$3 billion a year they spend on real estate agents – would also be reduced, because agent fees are mostly calculated as a proportion of rent. This would cause pain for agents, but many of their activities – inspecting properties, handling eviction proceedings, conducting marketing campaigns – are not needed in a pandemic. JobKeeper payments could support their businesses.

Read more: JobKeeper payment: how will it work, who will miss out and how to get it?

The biggest pain would be the interest outflow. But let’s reduce or suspend interest too, for both owner-occupiers and landlords. This would reduce income for banks, which would have a problem when their own liabilities to whole funders come due.

And at that point a really useful negotiation could take place between banks and the Australian government. They could “sit down, talk to each other and work this out” – as the PM has suggested to millions of individuals – to keep finance operating, in return for reformed service and a public equity stake.

In ordinary times, rents and interest have a controversial role in the economy. They extract value from productive actors in the economy for the benefit of owners of property and financial assets, and are the object of speculation. But, as the political economist David Harvey observes, they also have a co-ordinating role that drives competition and future production.

But these are not ordinary times. For the moment, at least, we don’t need rent to co-ordinate what the economy must do. We need to produce the essentials and whatever else can be safely done at home, with the rest of production in hibernation. And we need to ensure households retain enough income for the essentials, with reductions in income equitably shared.

Chris Martin, Senior Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW