By Susan Thompson, Professor of Planning, City Futures Research Centre.

What’s good health got to do with equity?

Good health depends on both our individual physical characteristics and how we live our lives. Genetics, age, ethnicity and gender are things we cannot simply decide to change. Our lifestyle is different – we can choose to live in a particular way – or can we? Is it really that simple to decide to live a healthy life? What if you can only afford to buy or rent a home located on a busy, noisy road? What if this neighbourhood has no footpaths or places to safely ride a bicycle? What if public transport is infrequent and unreliable and you can only get to school, the shops and to visit your friends by car? What if there are no parks nearby and you don’t feel safe walking along your street? Will that influence how healthy and well you are now and into the future?

Enjoying good health from birth to old age is dependent on a complex set of issues, many of which are outside of an individual’s control. These are known as the social determinants of health – the conditions into which people are born, live, work and grow old (WHO, 2018). These determinants are more important than medical care for the general health and well-being of the population (Wilkinson and Marmot, 2003). People who have low incomes, do not (or cannot, due to family circumstances) stay on at school, and (often) as a consequence of low educational levels, are unable to get long-term, secure employment are much more likely to die younger and suffer greater rates of illness, compared to those who are wealthier, better educated and in rewarding and lucrative jobs.

It is in everyone’s interests to address these disparities. Poor health for the individual results in greater health care costs for everyone. Inequities also have significant implications for the strength of the broader economy, as well as social life and community cohesion (Friel, 2016).

Health in Australia and its relationship to equity

In many respects, Australians are healthy. The nation enjoys one of the highest life expectancies in the world. For boys born in 2016, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates that they will live to be at least 80 years, and for girls, the estimate is almost 85 years (AIHW, 2018). However, these estimates don’t tell the full picture because many of us will live with a physical or mental disability, or chronic illness for those final years of life. These figures are also silent on the unevenness of good health across the nation. In particular, Indigenous Australians, residents in rural and remote areas, and those from poor socio-economic backgrounds tend to have a lower life expectancy, higher rates of sickness and more risk factors for illness than other Australians. For example, people in regional and remote areas are more likely than their city counterparts to smoke daily [22% compared with 15%], be overweight or obese [70% compared with 60%] and have high blood cholesterol [37% compared with 31%] (AIHW, 2014). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders have lower life expectancies than non-Indigenous Australians. In 2010-12, for males this was nearly 11 years less and for women it was just under ten years (AIHW 2016a). Psychological distress was much higher in these communities, as were related rates of suicide. In general terms, those with wealth and power have much better health outcomes than those in poor and deprived situations.

Addressing health and equity

To improve the health of all population groups, we need to address the social, political and economic inequities of access to health supportive conditions. The Settlement Health Map is a useful way of conceptualising what these are and how they are inter-related. Based on theories of the social determinants of health, environmental sustainability and urban planning, the Settlement Health Map brings together the socio-political, economic and environmental factors to explain the complex web of influences on human health (Barton, 2017; Barton and Grant, 2006). People are at the centre of the Map which, as a whole, is situated within the global ecosystem upon which all life is ultimately dependent.

Source: Barton and Grant, 2006.

Let’s consider some of these conditions and how they impact upon equitable access to a long and healthy life. The evidence from both built environment and health research and practice shows how much our health depends on the environments where we live, work and play and HOW we interact and use those environments – from global ecosystem to our local neighbourhoods; across physical and socio-cultural factors.

Where and how people live

Good health starts at home. This is the place that provides shelter for us to undertake our personal care needs – sleeping, eating and bathing. This is also the place where social and emotional needs should be met. People with reasonable, reliable incomes are in a better position to afford well-designed and robustly constructed accommodation that meets these requirements. For those struggling financially, costly housing is a significant burden. If accommodation can be obtained, paying for it will often mean not being able to afford other necessities, sometimes as basic as food, medicines or clothing. Turning off heaters in the cold and air-conditioners when it is hot, is another cost cutting measure often endured by low income households so that they can meet rental or mortgage payments. These deprivations can all have adverse impacts on health.

Housing design and construction have health implications. Poorly constructed housing can put occupants at risk of an accident, as well as being susceptible to weather extremes – rain, cold and heat.

Housing location can also impact upon health. Residential areas that adjoin noisy roadways or are under airport flight paths expose families to noise and air pollution which can lead to sleep deprivation and stress, both risk factors for many chronic diseases. More spread out neighbourhoods, particularly those on the fringes of our cities, are arguably not as healthy. This is where houses and apartments may be cheaper, but often require those living there to endure long commutes to get to work. Sitting for many hours in a car takes away from time to be physically activity (something we all need to do on a daily basis to keep healthy), as well as time with children and communities. These negatives for health can, to a certain extent, be offset with expansive backyards for independent children’s play and gardening, including growing fruit and veggies and keeping chickens. These are important food sources and for those struggling to make ends meet, can mean the difference between an affordable nutritious meal every night of the week, rather than on the odd occasion. Pets, which have numerous benefits for physical and mental health, are also a positive aspect of suburban life.

For those who can afford to live closer to work and all the services needed each day, chances are it will be easier to incorporate some physical activity, such as walking or cycling, to get around. And because distances are shorter, there will be more time to enjoy recreation and stress-free time with loved ones. But there can be a downside. These are the localities where we find higher residential densities with neighbours separated by a wall or floor. Poor apartment construction can result in noise nuisance from one household to the other, and in some housing complexes, there are restrictive rules which can impinge on personal autonomy, giving rise to psychological anxiety and stress.

How people get around

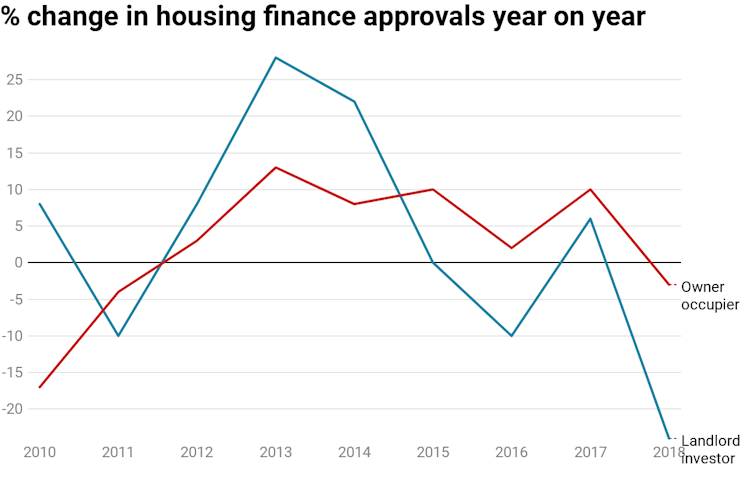

The transport we regularly use is another key factor in keeping us healthy. Sedentary and car dependent lifestyles make it difficult to be physically active – one of the most important ways of protecting people from chronic illness, such as heart disease and stroke, diabetes, and colon and breast cancers. Physical activity also lessens the impact of clinical depression and anxiety. The most disadvantaged Australians tend to do insufficient physical activity and as well, they are more likely to be obese compared to people living in wealthier areas (AIHW 2018). These trends are directly related to higher rates of disease as shown in the following charts.

The first chart shows the burden of disease and physical activity rates broken down for socio-economic area and gender (source: AIHW, 2018, p191). This is expressed as a ‘DALY’ which means ‘disability adjusted life years’. This is an measured estimate of the years of healthy living lost due to disability and mortality.

The second chart shows the burden of disease associated with obesity and socio-economic status (source: AIHW, 2018, p189).

Active travel gets people moving – both from place to place and in terms of their own physical activity. Public transport use, walking and cycling – either on their own or in combination – are forms of active transport. Those living in areas that are well serviced by regular, safe and affordable public transport have the best opportunity to be active. It has even been found that catching public transport connects communities, improving social interaction and cohesion (Allen and Allen, 2015). Inevitably, places well served by public transport are expensive. In far flung cheaper suburbs, buses tend to be infrequent and many localities do not have a train or tram line. This is where long commuting distances in cars are the norm. This is also where there are less people out and about, making it unsafe, especially at night. This then reinforces people’s hesitancy to go for a walk or bicycle ride – either for transport or recreation. Walking and cycling infrastructure is increasingly found across our cities, but if not well maintained, near to desired locations, and complimented with amenities such as shading in summer, lighting at night, easy-to-read signage, water fountains and public toilets, then the chances of it being regularly used for transport or enjoyment are diminished.

Further exacerbating the inequities of access to health supportive active transport, are the health risks associated with car dominated areas. These are principally air and noise pollution, and traffic accidents. On average, poorer communities experience higher concentrations of air pollution and greater exposure to noisy traffic than their wealthier counterparts. It has also been found that traffic accidents have a greater adverse impact on deprived populations (Allen and Allen, 2015).

The provision of green open space

Regular access to quality and well-maintained green open space is critical for good health. There is a raft of international evidence that definitively demonstrates how important this is for both physical and mental health across the life course (Townsend et al, 2015). It is therefore disturbing to see Australian research that shows areas with a higher percentage of low income residents have less green space than those areas where wealthier people live (Astell-Burt et al., 2014). Town planning policy has a strong focus on the provision of green open space, but as cities density and become home to more and more people, the pressure on land prices increases. This makes it difficult to provide sufficient open space easily accessible to everyone. In Sydney, for example, there has been an emphasis on ensuring access to the beautiful Harbour is not only available to the rich. However, while public access to the Harbour foreshore is a great initiative, those living in close proximity tend to be the prime beneficiaries on a daily basis.

Social connection

A healthy built environment is one that supports a sense of community and belonging. This fosters perceptions of personal security, confidence and comfort. In turn these feelings can encourage people to be physically active in their local neighbourhood – irrespective of its proximity to the city centre and independent of their socioeconomic status. A lively street increases the chance of incidental social interaction, enhancing possibilities for human connection and caring. This reduces feelings of loneliness and isolation, benefiting mental health. The built environment can also support community creation by providing opportunities for street activities. Things such as food and bush gardens, seating overlooking natural vistas, local playgrounds for children and their carers, and neighbourhood meeting places. But these facilities must be implemented with an appreciation of the diverse characteristics and needs of the locals. Without this, and community involvement in these initiatives, they can flounder. Community gardens can be a great way to bring culturally diverse communities together, irrespective of income levels, providing healthy opportunities for being physically active, socially connected and having access to healthy and cheap fresh food (Bartolomei et al 2003).

Getting healthy food every day

Access to fresh and nutritious food is critical for health. Below recommended levels of fruit and vegetable consumption (see Australian Dietary Guidelines: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines) is associated with obesity, a key risk factor for many chronic diseases. There is evidence that links low incomes and deprived neighbourhoods to ready access healthy food. Correlations have also been found between low income areas and the availability of fast food outlets (Allen and Allen, 2015). In an Australian study of healthy food availability in Sydney supermarkets, it was found that prices were reasonably even across the socio-economic divide, but the quality and variety of produce – both fruit and vegetables – varied. In underprivileged locations, the quality was poorer and there was less choice compared to wealthier suburbs (Crawford et al., 2017).

How can we ensure that everyone has an equal chance of being healthy?

While it is a complex picture, the places and spaces where people live their lives, together with the social, cultural and political environments, directly impact physical and mental health. The impacts – both positive and negative – are unevenly distributed – with those at the bottom end of the socio-economic scale experiencing much poorer health on every level than wealthier communities. We need to ensure that there is good urban planning as well as governance systems in place that champion equity to ensure a fair go for everyone – from birth to old age.

The most effective health interventions will be tailored to place and those residing there, respecting that individuals of different genders, ages, socioeconomic status and cultural backgrounds will have varying responses to interventions. Built environments are therefore not only implicated but vital in shaping better health outcomes. (Thompson and Kent, 2016, p92)

References

Allen, M. & Allen, J. 2015, ‘Health inequalities and the role of the physical and social environment’, Chapter 7 in Barton, H., Thompson, S., Grant, M., & Burgess S. (eds), 2015, The Routledge Handbook of Planning for Health and Well-Being: Shaping a sustainable and healthy future, Routledge: London: 89-107.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014, Australia’s health 2014, Australia’s health series no. 14. Cat. no. AUS 178. Canberra: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2016, Australia’s health 2016, Australia’s health series no. 15. Cat. no. AUS 199. Canberra: AIHW.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018, Australia’s health 2018, Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW.

Bartolomei L.A., Judd B.H., Thompson S.M. & Corkery L.F., 2003, A Bountiful Harvest: Community Gardens and Neighbourhood renewal in Waterloo, NSW Government, New South Wales.

Barton, H. 2017, City of Well-Being: A Radical Guide to Planning, Routledge: Milton Park.

Barton, H. & Grant, M. 2006, ‘A health map for the local human habitat’, Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, 126(6): 252–253.

Crawford, B., Byun, R. Mitchell, E. Thompson, S. Jalaludin, B. Torvaldsen, S. 2017, ‘Socioeconomic differences in the cost, availability and quality of healthy food in Sydney’, Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 41(6): 567-571.

Friel, S. 2016 ‘Social determinants – how class and wealth affect our health’, The Conversation, September 1, 2016: https://theconversation.com/social-determinants-how-class-and-wealth-affect-our-health-64442

Thompson, S.M. & Kent, J.L. 2016, ‘Healthy Planning: The Australian Landscape’, Built Environment, 42(1): 90-106.

World Health Organization, 2018, Social determinants of health. World Health Organization, Geneva, http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

Wilkinson, R. & Marmot, M. (eds), 2003, The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health, WHO, Europe: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/98438/e81384.pdf