By Julie Lawson, RMIT University and Laurence Troy, UNSW. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Despite recent falls in the housing market, housing costs and indebtedness bite deeply into household budgets, especially at Christmas time. Just over 433,000 households confront housing stress and homelessness every day across Australia. They represent the current shortfall of social housing.

If Christmas offers a moment for reflection, ask yourself what should our resolutions be for the housing market? What should we expect our governments to do about it?

In this article, we look at this week’s major statement on housing policy from a key contender to lead Australia’s next government – made by Bill Shorten at the ALP national conference.

We applaud the principle of fairness and the ambition of the ALP policy. We are less supportive of the reliance on for-profit investors, market rent mechanisms and land grabs. Our research shows direct government investment in social housing is ultimately far more efficient and effective than subsidising investors in the long term.

So what is Labor’s policy?

Shorten’s announcement also pledges reform of tax concessions that are driving inequality between households and investors. However, Labor recognises that this might not be enough to tilt the balance in favour of low-income households, and directing the savings from these changes into housing programs is a welcome move.

Labor proposes to subsidise investors in affordable rental housing, much like the Rudd government’s National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS). Labor would offer an $8,500-a-year subsidy over 15 years to investors who build new homes for low-income and middle-income households to rent at an “affordable” rate – 20% below market rent.

Starting modestly, the program aims to produce 20,000 affordable units over three years, building to a much larger target of 250,000 dwellings over ten years.

State governments would also be required to get on board through partnership agreements, as they have done in the past, providing land and other forms of co-investment. Hefty stamp duty revenues in recent years should make this easier for the states.

While Labor’s targets appear high by recent standards, Commonwealth and state governments directly funded the building of 9,000 public housing dwellings each year for the better half of the 20th century – until 1996. Annual production is now down to 3,000 dwellings. That’s not even enough to maintain the existing public share of housing.

Since the mid-1990s, a preference for outsourcing social responsibility through private rental providers and indirect rental support payments has dominated public policy. The ALP’s subsidy-based policy continues this trend.

The proposal centres on maintaining returns to investors at levels that encourage investment. As our previous research has shown, over the longer term this increases cost per dwelling. The question remains, as it did under the NRAS: who are we trying to subsidise here, the investors or the tenants, and is it really equitable and effective?

What are the alternatives?

Previous work has shown that NRAS-type schemes offer most benefit to new affordable housing developments when the funds are directed to not for profit organisations, rather than “leaking” out to the for-profit private sector. The advantages of this approach include:

- subsidies are retained within the affordable housing system

- benefits are directed to regulated not-for-profit developers with a social purpose

- the benefit is stretched out over a longer time, meaning government investment does not expire after a set time.

In the UK, a lack of direct conditional investment and weak definitions of affordability led to an 80% decline in social housing production. Without public equity, recurrent operating subsidies have no influence on design quality or ongoing impact after the expiry of providers’ obligations – or their cancellation. Yes, they can be switched on and off like a tap – as happened in 2014 with the NRAS.

With good design, a new scheme could overcome some of these deficiencies. Labor promises to provide lower annual subsidies than NRAS but for longer – 15 rather than 10 years – adding up to at least $127,500 from the Commonwealth for a tenancy to be offered at below market rents. It’s a substantial commitment.

Yet if this level of support was invested up front to build dwellings, rather than provided as an annual operating subsidy, it would make a substantial and enduring contribution to Australia’s housing needs. This is not only socially responsible, it can drive green innovation and is also more financially responsible too.

The only thing that stands in the way is the narrow public accounting doctrine that privileges day-to-day expenditure over long-term investments. This is something that, in the UK, even the Treasury and the National Audit Office are learning to overcome after the painful experience of the Private Finance Initiative.

How much more cost-effective is direct investment?

If equity and fairness are to be the yardsticks of policy, age pensioners, people with disabilities and low-paid workers should be the focus of our deepest support. Our AHURI research has established the level, type and location of investment required to meet the needs of 433,000 low-income households in housing stress or homeless across Australia. The current market offers no affordable or secure options for them.

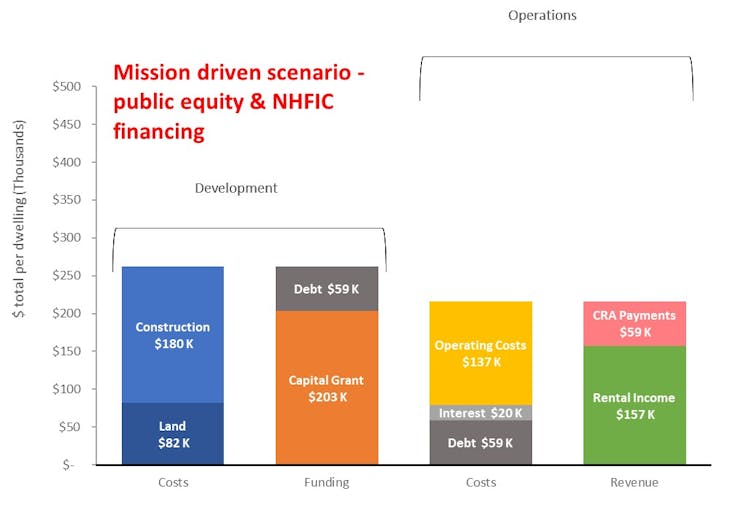

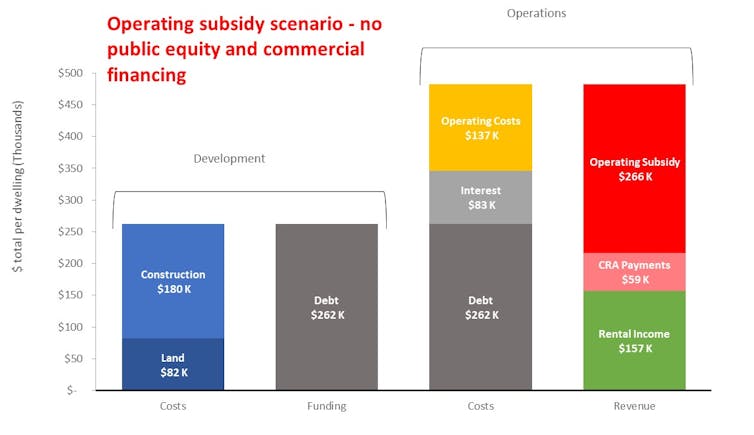

Our research also compared the cost of subsidising investors versus direct investment by government. Our modelling of costs and review of international experience provide evidence that direct investment is far more efficient and effective in the medium and long term.

Lawson et al, 2018, Author provided

Lawson et al, 2018, Author provided

Thus, we argue for more direct investment in social housing, strategic use of efficient mission-driven financing and retained investment via public equity and public land leases.

Recognition of the need for national leadership and policy reform is growing. After backpedalling, the Coalition government moved forward in 2018 to establish, with cross-party support, the National Housing Finance Corporation. This mission focused public corporation will soon channel lower-cost financing towards regulated not-for-profit housing. Of course, financing is debt and not quite the same as funding.

The Australian Greens have yet to announce their policy but an outline suggests a commitment to invest in social housing and establish a federal housing trust.

The ALP’s proposals are framed in line with the laudable principle of fairness and are a work in progress – rather than mission accomplished. Overcoming the shortfall of affordable and secure housing will require purposeful Commonwealth and state government funding, mission driven financing as well as land policies to make housing markets fairer for all.![]()

Julie Lawson, Honorary Associate Professor, Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University and Laurence Troy, Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW