By Hal Pawson

After more than six months of Parliamentary wrangling, the ALP’s flagship housing future fund bill finally cleared the Senate last week. For Australia’s neglected social housing sector, this presages a welcome revival of federally-supported capital investment, absent for most of the past quarter century. But, in a longer-term perspective, the resulting program will be significant only if it forms an initial downpayment on a much larger and broader housing reform and investment program.

How far will $10 billion stretch?

Under the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF), government will invest $10 billion on the capital markets to generate income hypothecated to social and affordable housing development subsidy. Resulting expenditures are officially anticipated as enabling construction of ‘30,000 new social and affordable houses in [the HAFF’s] first five years’.

Thanks to Senate crossbench advocacy, any shortfall in fund earnings due to capital market volatility will be topped-up from general revenue to guarantee $500 million in annual disbursements.

I’ve attempted elsewhere to explain simply how the HAFF model may work in practice. I say ‘may work’ because, while initially unveiled in 2021, Labor has remained coy on the scheme’s costings and mechanics. Therefore, a degree of speculation is unavoidable.

As Peter Mares has suggested, official reticence here probably reflects reluctance to expose the reality that the HAFF model, as inferred, will quickly exhaust its capacity to underpin new development dedications. Having committed to the initial tranche of investment contracts with housing providers (summing to 30,000 new units), program expansion will be therefore halted.

Only after HAFF-generated annual housing subsidy payments pledged in years 1-5 (but ongoing beyond that) have enabled the full repayment of construction debt by contracted housing providers will it be possible for government to dedicate subsequent HAFF returns to a follow-on tranche of newly contracted projects.

Under the small-scale NSW housing future fund, believed to have inspired the HAFF, standard contract terms are 25 years. However, according to the Grattan Institute’s Brendan Coates, it might be possible for subsidy-recipient housing providers to extinguish construction debt in as little as 15 years, implying that a new round of social and affordable development contracts could be struck from year 16.

Equally, IF 6,000 homes per year is what can be supported by a capital stake of $10 billion, IF government believes this an appropriate annual scale of construction, and IF ministers insist on funding social and affordable construction under this model, government would need to commit at least another $20 billion to the HAFF to enable a continuation in the initial flow of new development commitments in years 6-15. If subsidy contracts, in fact, need to run for 25 years, the ‘gap’ would implicitly call for a $40 billion HAFF top-up (i.e. $10 billion more every five years).

Why does all this matter?

All of this matters because, as many have rightly noted, the HAFF subsidy commitment as announced will underpin a program equating to only a very small fraction of Australia’s total unmet need for social and affordable housing.

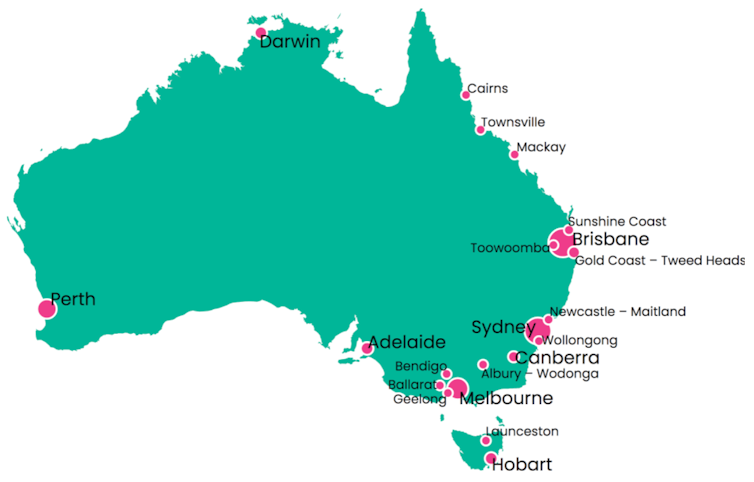

Even if re-funded to form a continuous program of new commitments extending beyond year 5, the scale of activity envisaged under current HAFF plans is modest relative to, for example, the 175,000 qualifying households registered on state/territory public housing waiting lists. And our own census-based estimate that also factors in households on slightly higher incomes but still in rental stress puts total unmet need for social and affordable housing at 640,000 units.

Therefore, a 30,000 program (of which only 20,000 will be social housing affordable to those on the lowest incomes) is going to make only a small dent in the problem. And that’s before you factor in the growing housing need that accompanies a growing population.

These are the reasons that some advocates call for 25,000 new social housing units per year. Beyond this, one of Australia’s largest unions has recently put forward a reasoned – and funded – case for an annual program of 53,000 homes.

Even the smaller of these numbers appears huge relative to the current HAFF plan but, for context, it would account for around 12-13% of Australia’s total housebuilding – somewhat below the 16% represented by public housing construction in the period 1945-70. In England, meanwhile, not-for-profit housing associations today contribute around 25% of total housebuilding, albeit that this includes homes for market sale as well as for social rent.

What else is Labor offering – and where is it falling short?

To be fair, the Albanese government has also committed to several initiatives directly relevant to social and affordable housing supply over and above the HAFF. Firstly, under the National Housing Accord, mainly concerned with enabling expansion of overall housebuilding, the Commonwealth is pledged to fund 10,000 new affordable rental homes in addition to the HAFF 10,000.

Secondly, apparently thanks to pressure exerted by the Senate crossbench, Minister Collins in June committed to a $2 billion social housing accelerator fund directly funded from general revenue. This might generate 5,000 additional new dwellings over a couple of years.

Thirdly, as part of the parliamentary deal that eventually secured the passage of the bills through the Senate last week, government pledged another $1 billion to supplement the existing National Housing Infrastructure Facility. However, while NHIF assistance may be provided via grant, it is largely a financing and not a funding vehicle – i.e. a source of cheap debt to enable social and affordable housing development.

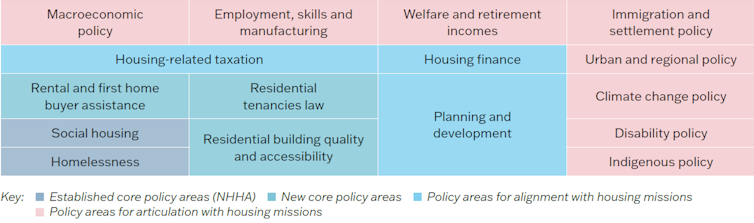

More broadly, delivering on other elements of its 2022 election platform, Labor has also implemented significant enhancements to national housing policy architecture; in particular, the re-establishment of a National Housing Supply and Affordability Council and the upgrading of a national housing delivery agency, Housing Australia.

What is badly needed at this point is a framework to lend coherence to the initiatives already delivered since the election and – more importantly – to provide a roadmap for the much wider and more ambitious housing reforms Australia badly needs.

Being already committed to a 10-year national housing and homelessness plan (NHHP), it would be hoped that this kind of framework is something Government already has in hand. However, while its development process is still at a relatively early stage, there are serious concerns that the NHHP could fall far short of what’s needed. To consolidate its housing policy progress to date, and to lock in a positive trajectory for the future it’s vital that this process is put back on track.

This story was first published by John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations. Read the original story here.