By Chris Martin. Originally published in ‘Reforming Residential Tenancies Acts’, a special issue of Parity magazine, by the Council to Homeless Persons.

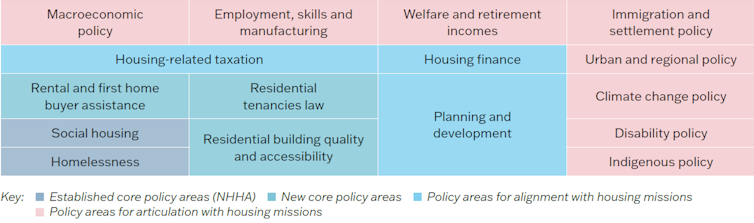

On 28 April 2023, Australian governments, meeting as the National Cabinet, agreed to develop a new law reform agenda to ‘strengthen renters’ rights across the country’. Housing ministers are now tasked with drafting proposals to take back to National Cabinet in the latter half of the year.

Although no details have yet been produced, the announcement of the national reform agenda is remarkable for two reasons.

First, the agenda is being developed in collaboration by states and territories, co-ordinated through a national forum. This contrasts with the experience of recent decades, when states and territories have almost always gone it alone when reviewing and revising their residential tenancies legislation.

The result is tenancy laws that are increasingly divergent, while gaps have gone unaddressed. The divergences include key topics, such as security of tenure and whether landlords can give termination notices without grounds. The ACT has recently amended its legislation to remove provision for without-grounds terminations, both at the end of the fixed term of a tenancy and during a periodic tenancy, while Victoria allows them only at the end of the first fixed term of a tenancy, but not for subsequent fixed terms or periodic (‘month-to-month’) tenancies. Queensland and Tasmania allow without-grounds terminations at the end of a fixed term, and not periodic tenancies, so tenants can be on a string of fixed terms and still face without-grounds termination. Other jurisdictions still allow terminations without grounds at the end of fixed terms and for periodic tenancies, although the new government in New South Wales has promised to remove them.

Figure 1. Without-grounds terminations across Australia: notice periods, where allowed

| NSW | Qld | SA | Tas | Vic | WA | ACT | NT | |

| End of fixed term | 60 days | 2 months | 28 days | 60 days | 90 days* | 30 days | Not allowed | 14 days |

| Periodic | 90 days | Not allowed | 90 days | Not allowed | Not allowed | 60 days | Not allowed | 42 days |

*60 days if the fixed term is less than 6 months. End of first fixed term only.

Another area of divergence is family and domestic violence (FDV). Until relatively recently, residential tenancy laws did not make any provision for tenants experiencing FDV. Over the past decade, all states and territories have amended their legislation to address FDV, but taken different approaches. Tenants seeking to stay and remove a FDV perpetrator can do so through FDV order proceedings in New South Wales, Tasmania and the NT, but elsewhere must apply separately to the tenancy tribunal to end the perp’s tenancy. If they want to leave a tenancy early and end their liability, they can give a notice certified by certain professionals in New South Wales, Queensland and WA, but must apply for court or tribunal orders in other jurisdictions. Three states have made changes the rules about tenants’ vicarious liability for damage and other breaches in FDV situations; in other jurisdictions, the usual rules still apply.

Figure 2. Family and domestic violence provisions across Australia

| NSW | Qld | SA | Tas | Vic | WA | ACT | NT | |

| T stays, removes perp | FDV order may terminate perp’s tenancy | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | FDV order may terminate perp’s tenancy | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | Apply to court, satisfy as to FDV | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to DV | FDV order may terminate perp’s tenancy |

| T leaves, ends liability | T may give notice with evidence/ certificate | T may give notice with evidence/ certificate | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | FDV order may terminate tenancy | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | Give notice with evidence/ certificate | Apply to tribunal, satisfy as to FDV | FDV order may terminate tenancy |

| Vicarious liability | Tenant not liable for FDV damage | Tenant not liable for FDV damage | Per usual | Per usual | Tenant may apply to dismiss FDV-related termination proceedings | Per usual | Per usual | Per usual |

It is not only on substantial issues that laws are diverging: residential tenancies legislation looks and reads differently across jurisdictions. For example, Victoria’s Residential Tenancies Act is about seven times the length of Tasmania’s, and only a little shorter than Melville’s Moby Dick. Although recent amendments have mostly improved the law for Victorian tenants, they have also made the Act a complex, difficult-to-navigate piece of legislation.

The second reason why the National Cabinet’s decision is remarkable is that it expressly states that the reforms should ‘strengthen renters’ rights’. This contrasts with the theme of ‘finding the right balance’ between landlords’ and tenants’ interests that has marked most state- and territory-level reviews, and which has tended to produce only modest improvements while bigger issues of housing justice go unaddressed.

Australian residential tenancy laws are generally very accommodative of landlords and their interests. They present no barrier to landlords entering the rental sector: no training, registration or licensing requirements – all you need is a dwelling to let. (All states and territories require that the dwelling must be fit for habitation, but the onus is on applicants and tenants to police this.)

Tenancy laws also generally allow landlords to exit the sector when it suits them to do other things with their properties, whether that’s selling, or using the property for their own housing or other purposes (e.g. Airbnb). Even those states that have removed or restricted the use of without-grounds terminations still allow termination on grounds such as preparing the premises for sale (Victoria and Queensland).

And as long as they are in the rental sector, landlords can increase rents in line with the general market level of rents for comparable premises. Most jurisdictions have limits on the frequency of rent increases (once in 6 or 12 months), but none limit the amount or rate of increase. The ACT has a legislated ‘guideline’ (1.1 times the rate of the rent index for Canberra in the Consumer Price Index), and landlords seeking rent increases above the guideline must apply to the tribunal and show the increase is not excessive to the general level of rents for comparable premises. This procedural step probably discourages increases above the guideline (which is a good thing), but it is not a firm cap on rents. The issue of rent increases has been conspicuously absent from state- and territory-level reviews.

Research commissioned by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) shows how accommodating Australian tenancy laws are of landlords.[2] In a survey of just under 1,000 landlords, a significant portion (44%) said tenancy laws were a ‘very important’ consideration in their decision to invest; however, of landlords who had disposed of a property, only 14% nominated dissatisfaction with tenancy laws as ‘very important’ to their decision – placing tenancy laws last among a range of possible factors in disinvestment decisions. By far more commonly cited ‘very important’ reasons for disposing of a rental property were ‘it was a good time to sell and realise capital gains’ (50%) and ‘I wanted money for another investment’ (47%).

The research also put to the test the claim that tenancy law reform causes landlords to disinvest. Analysis of rental bond records found no statistically significant increase in properties exiting the Sydney and Melbourne sectors around law reform events in those states (the commencement of the Residential Tenancies Act 2010 (NSW), and the start of the Victoria’s laws reform review in 2015). In fact, Sydney property exits were slightly lower after the New South Wales reforms.

The most striking finding of the research was how frequently properties enter and exit the rental sector – whether the law is changing or not. In both Sydney and Melbourne, more than half of properties exit within five years of entering the rental sector. Properties churn rapidly through the sector, as it suits their owners – and as a result tenants are churned out of their homes.

While past law reforms have not caused landlords to disinvest, a stronger law reform agenda that is less accommodating of landlords’ interests might have that effect – and that would be no bad thing. Among other reforms, the new agenda should strengthen tenants’ security by getting rid of without-grounds termination, narrowing the scope of termination grounds, and ensuring tribunals can decline termination where it is not justified or would result in homelessness. It should also regulate rent increases, by caps or an ACT-style guideline. Landlords can either meet these standards or leave – and if they do leave, that’s more room for would-be homeowners or for a different, better type of rental housing provider.

The Senate is currently conducting an inquiry into the worsening rental crisis, including issues of renters’ legal rights. To make a submission to the inquiry, see the inquiry website. Submissions close 4 August 2023.