By Dr Mireia Montes

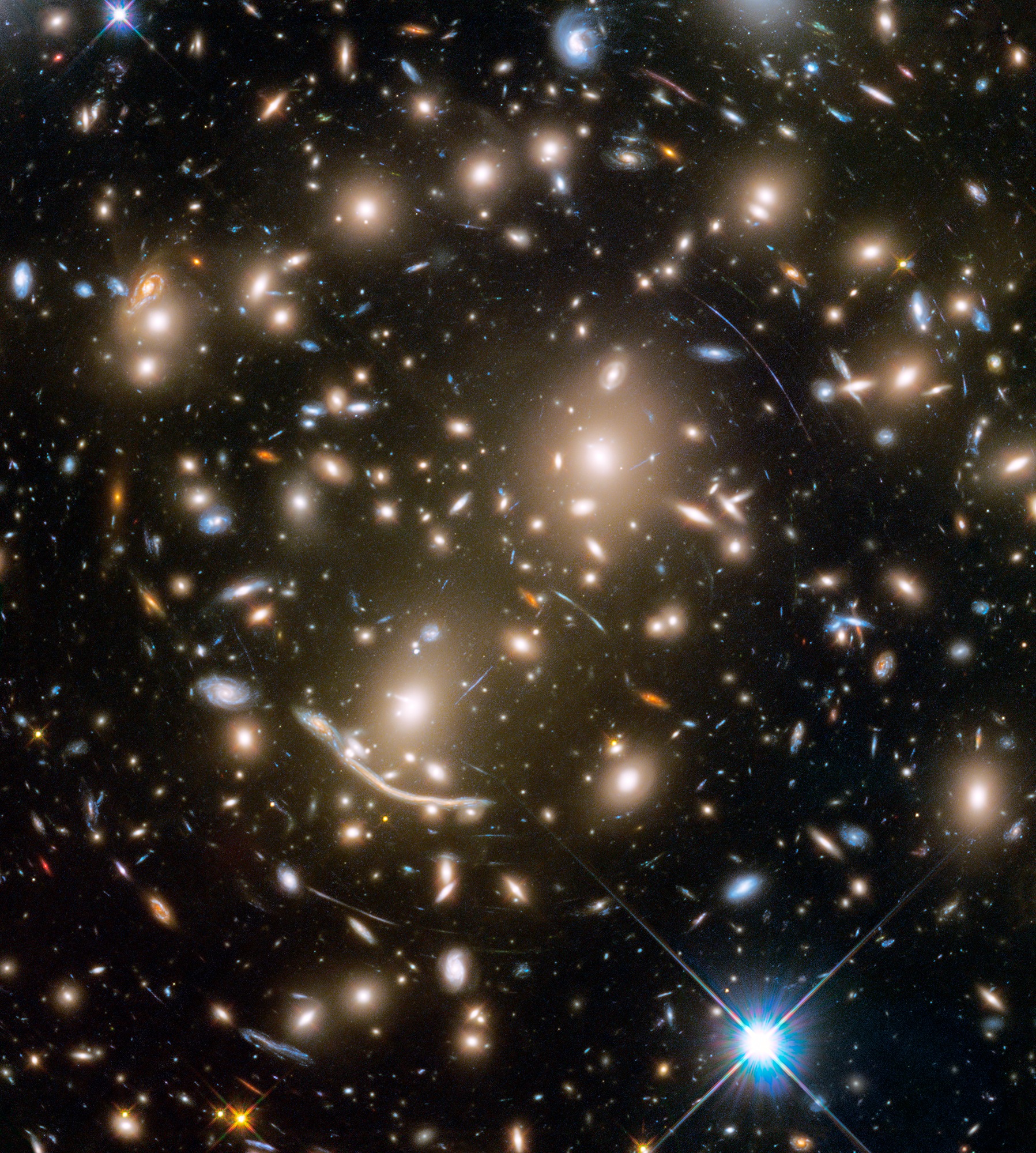

Using the Hubble Space telescope’s past observations, astronomer Dr Mireia Montes’ group demonstrated that intracluster light—the diffuse glow between galaxies in a cluster—traces the path of dark matter, illuminating its distribution more accurately than existing methods.

Image Credit: NASA, ESA, Jennifer Lotz and the HFF Team

Galaxies are collections of millions of stars, gas and dust hold together by gravity. They also contain the mysterious, dark matter. Although dark matter makes up most of the mass of the Universe, we can only see dark matter through its effect on normal (baryonic) matter. UNSW Women Science champion Mireia Montes and her collaborator Ignacio Trujillo however have found a new way to see the location where the dark matter should be using intracluster light–a byproduct of interactions between galaxies in clusters.

Like humans, galaxies don’t like to live alone and tend to gather in groups (containing tens of galaxies) or clusters (hundreds to thousands of galaxies). As you travel away from the centre of a cluster of galaxies, it is increasingly dominated by dark matter. Interestingly this is also where you find the intracluster light. Dr Montes and Trujillo showed that by mapping intracluster light, this very faint glow could indicate how dark matter is distributed as it has the exact the same gravitational potential.

Image credit: NASA, ESA and M. Montes

To test this, they used the images of the Hubble Frontier Fields. The Hubble Frontier Fields program was a deep imaging initiative designed to use the natural magnifying glass of galaxy clusters’ gravity to see the extremely distant galaxies beyond them, and thereby gain insight into the early (distant) universe and the evolution of galaxies since that time. Interestingly, at the time, intracluster light was considered an annoyance for these kind of studies as it made it more difficult to identify the distant galaxies beyond. Dr Montes and Trujillo however have shown that this “annoying” faint glow could actually shed significant light on one of astronomy’s great mysteries: the nature of dark matter.

When asked what is next, Dr Montes said “Now it is time to extend this project to more clusters, further away from the centre of the cluster and see if in other objects, groups of galaxies or even galaxies, this result is still true.”

Read more about the MNRAS journal article: ‘Intracluster light: a luminous tracer for dark matter in clusters of galaxies’.

Follow Mireia on Twitter

(Based on the UNSW press release from Ivy Shih)