By Dr Poppy Watson

When I tell people that I work as a researcher in the School of Psychology they tend to be quite baffled. “Does that mean that you treat patients?” they often ask. I have to tell them that I am not at all qualified to treat patients (even though I have a PhD in Psychology). Psychology is such a broad science, it really is not surprising that there is so much confusion out there.

The Australian Psychological Society defines Psychology as “both a science and a profession, devoted to understanding how people think, feel, behave and learn”. Depending on whether you are interested in the science or the professional side of things will determine the career path you take.

A clinical Psychologist treats patients: Becoming a professional, registered clinical psychologist generally requires a Psychology undergraduate degree, followed by either more specialised educational courses (e.g. a clinical Masters programme) or supervised on-the-job training. Clinical Psychologists see patients and might specialize in certain areas such as child psychology or sports psychology.

Academic Psychologists do research: If you are interested in a career in psychological research then you do the same Psychology undergraduate degree as clinicians but then generally go on to do a PhD, followed by post doctorate research jobs – always on the lookout for an elusive tenure track (permanent) position at a University or research facility. Some people take their expertise to go work in industry e.g., companies or government agencies who want to use evidence from psychological research to change behaviour/inform marketing practices etc.

Undergraduate degrees in Psychology are very broad – often encompassing everything from brain and behaviour (what we know about how animal and human brains function to drive observable behaviour), perception and cognition (attention, visual systems, decision-making, memory, language), childhood development (development of self and reasoning), social psychology (how groups behave/interact), psychopathology (mental illness, addiction), forensic psychology (decision-making in the context of the law) and the basics of research (good experimental design, statistics). Different universities will focus more on different areas depending on the specialties of the academics who are teaching. Related specialties such as neuroscience (study of the brain and nervous system) will often fall under the department of Psychology but will sometimes be a separate department/degree.

During a PhD you generally become skilled in carrying out research, focused on specific research questions that relate to one or more of these topics above. You might develop more lab-based skills (particularly if you go into neuroscience) or you might gain experience with neuroimaging techniques such as MRI scanning and electroencephalography (EEG). You might study how different cognitive systems (attention, memory) are affected in disorders such as schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s or, as I did, study how learning about reward influences the everyday choices that we make. Although the potential topics are infinite, most research projects are a series of experiments that generally have the same structure– reading literature, outlining hypotheses, thinking of a good experimental design (using the right paradigm, testing the right populations, ensuring the appropriate control groups), programming the experiments (e.g. you might need to present certain images on screen while you record eye gaze location), testing participants (human or animal), analysing the data (using simple statistical models or complex computational modelling) and then (hopefully) writing up the experiment for publication. As you move beyond your PhD towards becoming a full Professor (well, maybe eventually) you still do these things only now you are able to develop a wider program of research, mentoring younger researchers in your team who work on different, but related, research projects.

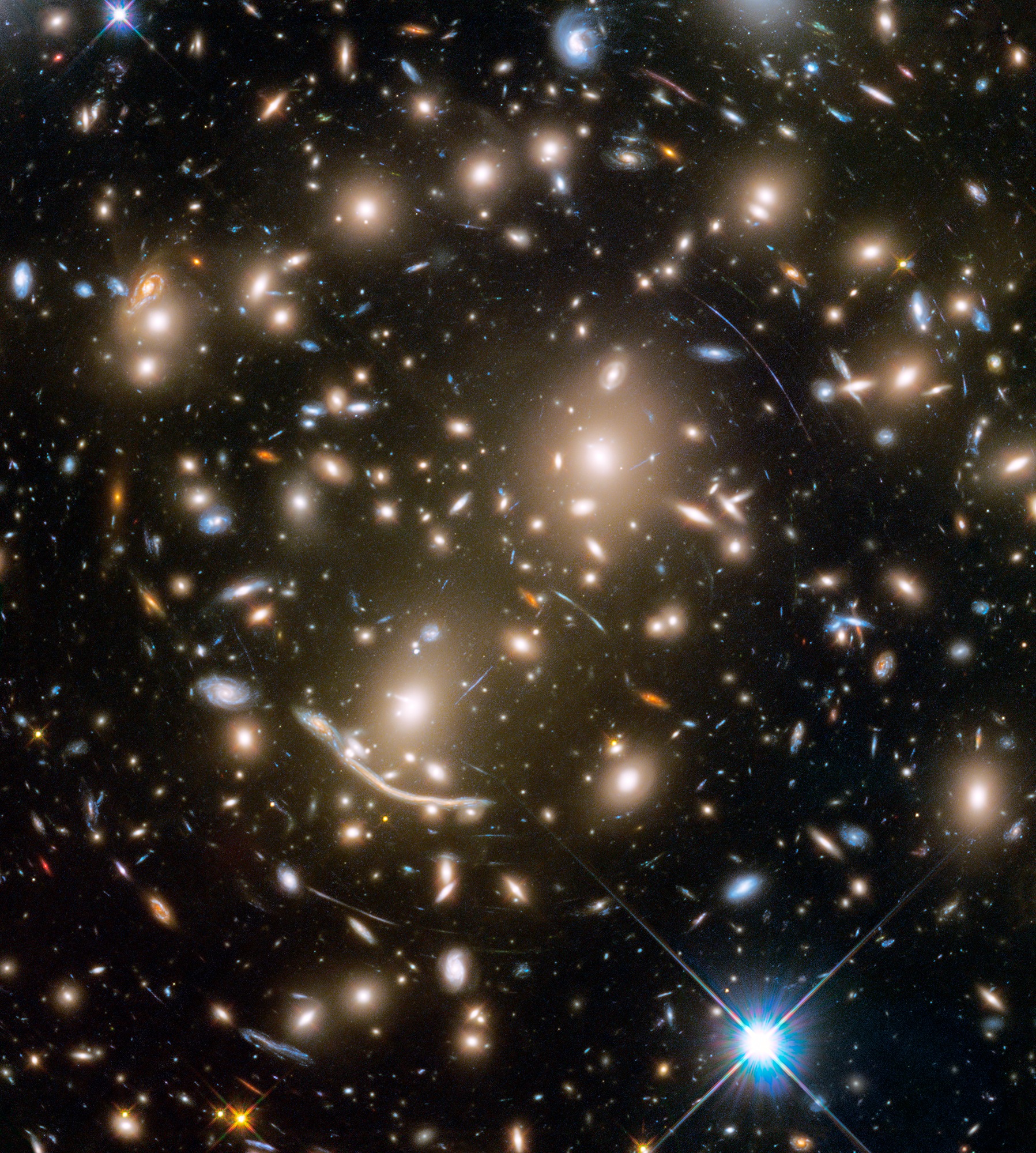

Some people are surprised that Psychology is a Science – perhaps because popular media would suggest that we are sitting around dreaming up fad diets, writing tips on how to win friends and influence people or having pointless philosophical debates. As the science of Psychology matures and technology becomes more sophisticated, we are recruiting physicists, mathematicians, computer programmers and biomedical scientists to help us in our endeavour to understand the human brain and behaviour.

Follow Poppy on Twitter