By Kristina Fidanovski

Emily, like many scientists, leads a double life. She doesn’t begin with that though. When she sits down for this interview, she has an easy smile and ready words to set me at ease (I’ve never interviewed anyone before), and at first she tells me about molecular genetics and cell biology. The Jazzercise comes later.

By day, Emily works on getting her PhD. Where that will take her, she’s not too sure yet. But for now, she looks at how genes can affect your metabolism through your immune system. Specifically, she’s looking at the genes inside a type of immune cell – the eosinophil – which lives inside fat and . There’s been a lot of hype around beige and brown fat recently, mostly because it’s a type of fat that burns energy. Some people have it, some people don’t. And that’s pretty exciting to think about in terms of how these cells could be activated and used as an obesity treatment. Emily says that the hype isn’t necessarily wrong or misinformed, it’s just early: we’re not there yet. Her work is on the fundamental end, she’s working on establishing the basic facts about eosinophils, their genes and how they interact with fat cells.

| An Average Day in the Life of Emily: Molecular Geneticist | |

| The Dreaded Commute | Check emails and get the day started. |

| Morning | Lab Time! Working with bacteria to grow some DNA and then extract it.

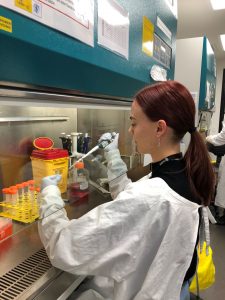

Outreach Activity: A fun 20 minutes of pretending not to be cold for a Women in STEAM photoshoot (a collaboration between women in science and art to capture the image of all types of scientists for a photo exhibit). |

| Lunch | Important networking time… that is, lunch with a couple of the lab buddies. |

| Afternoon | More lab time, this time to prepare the DNA for sequencing and send it off.

Some computer time analysing data, catching up on the latest in the field, or putting off working on those presentation slides you really need to do. |

| Evening | Freedom: for musical and athletic pursuits! |

But how did Emily come to be labouring away on a PhD anyway? She says that in high school she was just picking all the subjects she enjoyed. And those subjects happened to be chemistry, physics and biology (with some maths and English thrown in), even though her teachers were saying “Isn’t that too much science?” Emily didn’t think so. At university she did some general science and got really interested in molecular cell biology. She got more and more engrossed as each year passed until her third year conversations with PhD students hooked her into doing an honours project. It was in the same group she’s currently working in. When her honours year was coming to a close she says, “I felt like I had only just scratched the surface of my project.” So it felt natural to her to keep going and really dig into the fascinating world of ‘immunometabolism’.

It seems to be going well for her. She’s a recipient of the prestigious Scientia Scholarship, though she’s too modest to mention it. And she already has an international conference under her belt. Last year she presented a poster at an ‘Immunometabolism’ conference in Aspen, Colorado. She says it was really cool to finally meet the people whose names you see on papers. She also likes how easy it is to share ideas when you’ve all been brought together like that. This year she’ll be travelling again for an ‘Eosinophil’ conference in Portland, Oregon. She’s looking forward to it, not just because the travel part is fun, but also because she feels that meeting other researchers expands your thinking in ways that no other experience can.

Finally, I get around to asking her who she is when the lab coat comes off. The answer is “Jazzercise! The original dance fitness.” I learn that it was started 50 years ago and involves dancing to songs for exercise, with strength training at the end to make sure you really feel it in the morning. Emily likes exploring that totally different side of herself and she’s even been an instructor since last July. It’s certainly an unexpected and totally brilliant answer. I’m fascinated. It’s almost an afterthought when I also learn that she plays clarinet in the Kuringai Youth Orchestra. She is a hidden wealth of talents.

In the end I ask her about the UNSW Women in Maths and Science Champions Program. “It was always something that I wanted to try,” she says – interacting, connecting with young girls who might one day come to love science. She thinks that it’s sad a lot of young girls might not even consider science. “We’ve all been there, if we can be inspiring to them that’s pretty cool.” She feels that being a scientist is about more than just the science that happens in the lab, “We have to be communicators too.”

Follow Emily on twitter @EVohralik

Follow Kristina on twitter @Kris_Fidanovski

It was love at first sight for Kristina when she found her current research project at UNSW after multiple lab placement programs. Since then every day for her has been something like a wild quest into unlocking the secrets of the complex world of conductive polymers. Her research as an organic chemist strives to tame these somewhat uncooperative substances into forming therapeutic patches for patients suffering from heart-attacks. When she’s not in the lab pursuing these ‘funky plastics’, Kristina can be found either curled up cosily with a nice little book, having fun with friends, playing trombone in a band or travelling far and wide to her heart’s content.

It was love at first sight for Kristina when she found her current research project at UNSW after multiple lab placement programs. Since then every day for her has been something like a wild quest into unlocking the secrets of the complex world of conductive polymers. Her research as an organic chemist strives to tame these somewhat uncooperative substances into forming therapeutic patches for patients suffering from heart-attacks. When she’s not in the lab pursuing these ‘funky plastics’, Kristina can be found either curled up cosily with a nice little book, having fun with friends, playing trombone in a band or travelling far and wide to her heart’s content.