Disclaimer: all views are my own, this is an opinion piece meant to stimulate thought and discussion

When I decided to do a PhD in virology, I never expected to be working in ground zero during a pandemic. In January of 2020, news of an emerging virus from China reached Australia. This virus was similar to ones that had caused pandemics before; SARS and MERS. Original thoughts were that it would only cause severe symptoms in a low percentage of people, and would likely be similar to catching the flu. As the weeks went on, it became apparent that this virus was a lot worse than originally thought, and research rapidly changed to help control and treat SARS-CoV2.

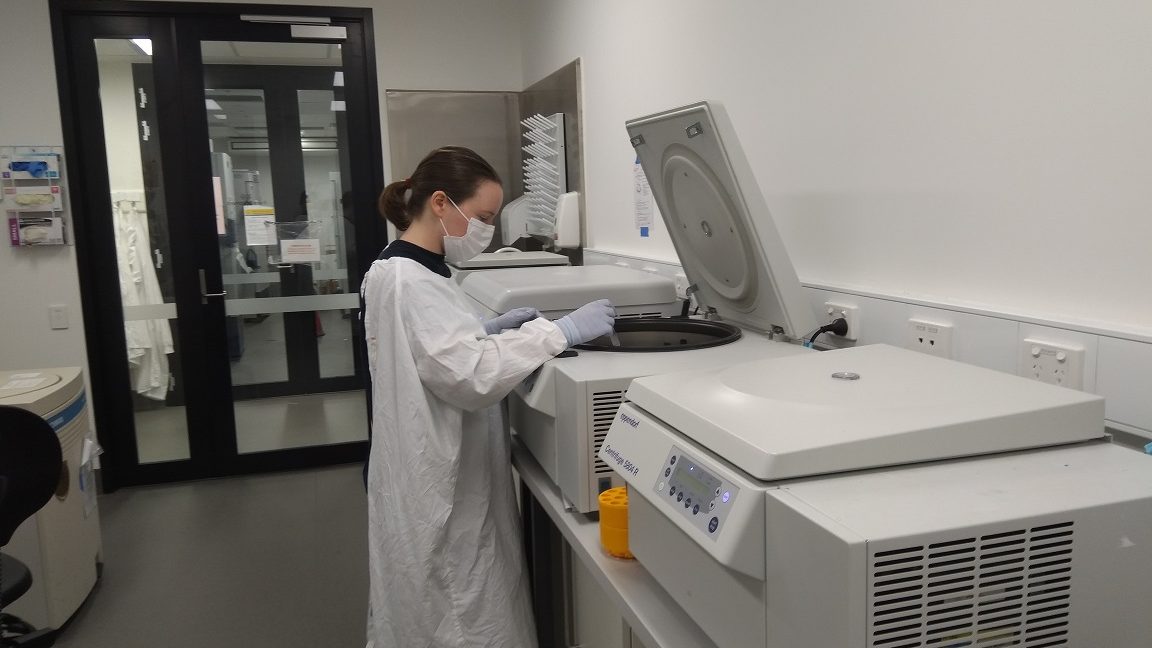

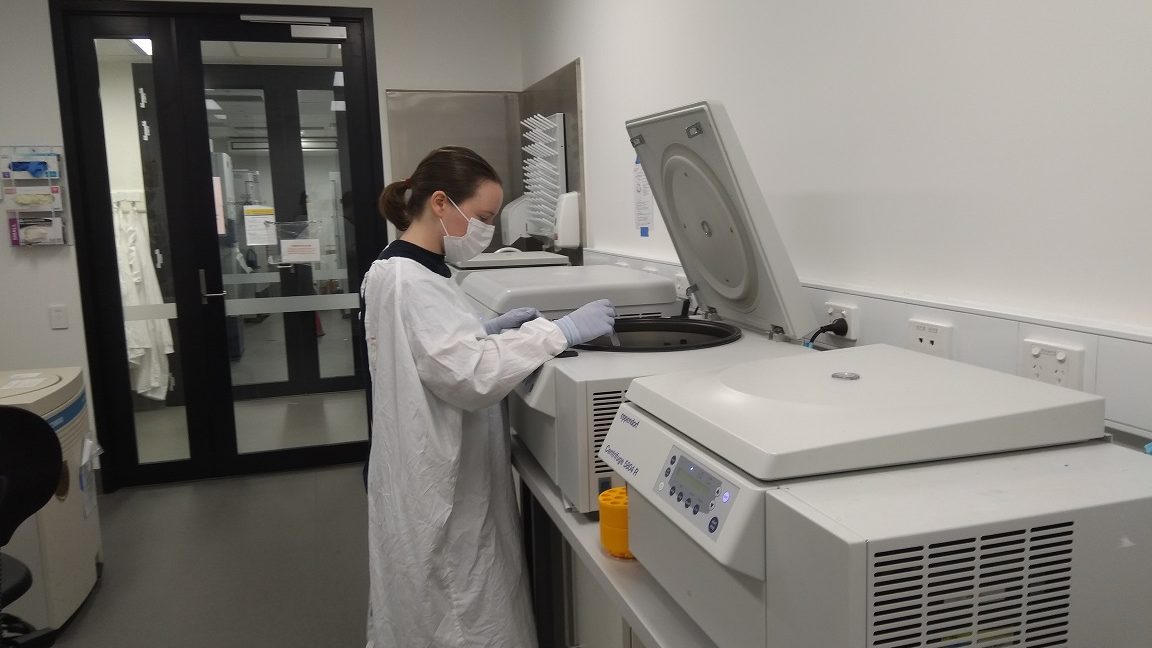

This included my laboratory. As the only virology lab in the faculty, all eyes were on us. And then the questions begun. I watched on in awe as my supervisor and peers were answering questions left, right and centre, and making recommendations and predictions. I had studied coronaviruses briefly in undergraduate courses, but had nowhere near the required expertise to be making statements or giving my opinion to the public… or did I?

As I watched the pandemic unfold, I realised that a lot of media coverage was incorrect or sometimes downright misleading. Many questions asked by the public I could easily answer, and recommendations including masks and sanitisation seemed straight forward to me. Over time I became aware of the huge knowledge gap between the public and the virologists and medical professionals dealing with the disease. Often the professors and doctors were overqualified for the questions they were asked, and it became clear that you either knew a lot about viruses, or next to nothing. There was no in-between.

Now, 1.5 years into the pandemic, I still get asked basic questions about the virus, disease and hygiene. Clearly, something is going wrong with science communication. Even with all public eyes focussed on viruses, we still can’t seem to get even basic information across.

So what is causing this lack of communication? Some of it comes from the academic culture, which is very much focussed on publishing papers and talking with peers. Academics present work at conferences targeted at very specific audiences, where the layperson or even bachelor graduate would quickly be left behind. Unfortunately, science communication is not taught or valued in academia anywhere near as highly as it should be. Concepts which are seen as basic knowledge to the microbiologist are not taught outside of university degrees, and not enough science communicators are around to explain them. Whilst there has been a marked increase in academics taking to social media and media outlets during COVID, especially on the topic of vaccine uptake, the message is still not as clear as it should be.

A second contributor to the communication divide is the rise of social media and the ease at which people can present their opinions to a wide audience. The lack of regulations or fact checking often means that misinformed or deliberately incorrect people can influence thousands of people at a time, which leads to the propagation of “fake news”. This was especially prevalent surrounding the origin of SARS-CoV2 and now the multiple vaccines and side effects. News and media outlets are not much help, often promoting agendas rather than aiming to educate and inform. In Australia, media has been very anti-vaccine in recent months, highlighting every case of side effect and sometimes over-exaggerating vaccine risks. The media single-handedly increased vaccine scepticism in a week, and registrations for immunisations reflect this.

As a budding virologist, I know that I am not the expert on these issues, however I know there is an extreme disconnect between the true experts, the researchers and the general public, and I know I can help. One thing I have learned during this pandemic is that no matter how little you think you know, any amount of information that you can educate on is better than nothing. Even clearing up the difference between a bacteria and a virus – something taught in high school biology – is a valuable contribution and the first step in eliminating the knowledge gap in science.

So this is a call for confidence. For those of you reading this blog article, you are more of an expert that you think. Whether you research chemical signatures of distant stars, gold nanoparticles, cholesterol metabolism or the biofouling of marine surfaces, you know more about a lot of science than the general person. Try and be an expert opinion, where you can. Try and help friends out with finding reputable sources, try and spread what you know to colleagues or on social media. As an individual, it may not be much, but as a community we can begin to change the stereotype of a scientist from a introvert in a lab coat to an approachable, knowledgeable person and help keep the public better informed.

Emma has been listed on the UNSW Sydney COVID-19 experts and is actively contributing to media requests and providing research and statements for interested parties.