By Greg Paine, City Futures Research Centre.

City Futures Research Centre and the Henry Halloran Trust recently hosted a seminar to review a Reserve Bank Australia discussion paper on zoning and house prices (see the video, and the CityBlog summary). It was well-attended (the issue strikes a chord), and conducted in the best traditions of scientific rigour – strong, even feisty, critique by peers, but also polite (the participants were happy to sit next to each other rather than be separated, as in debates!) – in an effort to get to “what’s what”. But on wandering home, a question lingered: have we actually got any closer to an answer and, given it didn’t seem like it, would more of the same help? Just what is going on here in this duelling of ideas and numbers and graphs?

An answer started to formulate when remembering the idea of the “wicked problem”, those issues that are so tangled up and recursive that usual limited-dimension problem-solving just doesn’t work anymore. The concept is now much talked about, though often forgetting that it was first described by two urban planners, back in the 1970s. City problems are inherently wicked.

And so maybe this RBA report, and the event itself, with its four economists (only, plus one urban planner) was itself inherently limited in its ability to reveal. Like the laboratory technician picking from a petri dish a strand only of the thing being investigated and putting it under the microscope. You get to learn a lot about that lonely strand, but little if anything at all about its wider operating context, how it influences that wider world, how in turn it is influenced, and whatever else there is out there we need to know. Too often, to make complexity manageable, we simply leave things out. The problem becomes “desiccated and dulled”, and isn’t the actual problem anymore. We also know, from neuroscientists’ ability to now map brain activity, that decision-makers (which is all of us) are not persuaded by facts and number alone. Sometimes not even a little bit, as explored in exquisite detail by the Utopia television show. As its author, Rob Sitch, explains, he is interested in that part of decision-making where the business case is actually not of interest (“runs out” as he puts it) to those involved. It is the resultant need for a more expansive connected view that the recent approach of “network science” for example seeks to address.

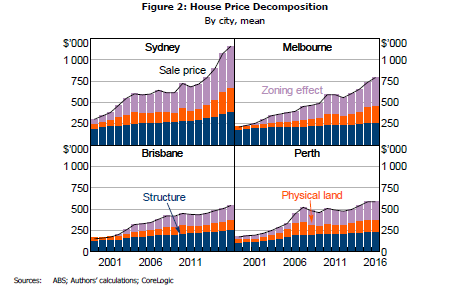

There were lots of graphs presented. One was key. It shows the cost of actually building a dwelling structure, plus the cost of land, with overall sale prices. The “gap” (or “wedge” as the RBA, perhaps provocatively, called it) was where the real debate took place. The RBA called it the “zoning effect” and considered it more or less as an impost. There was much discussion as to whether it comprised the “narrow” planning view of zoning as simply land use control (as in colours-on-the-planning map) or a more omnibus version including lot size, allowable density, and so on – ie. market interventions, or “planning”, overall.

Source: RBA.

There was less (though some) canvassing of what else this diagram could indicate. And how, looking at this space in a more networked way, there might be a whole lot more going on than revealed by a mere economic analysis of the three price criteria alone. Like how it might actually, and more accurately, represent the whole raft – and complexity – of personal and household lifestyle factors that are part of any decision (choice) about where and how to live? And, if factored in to any study, might yield far richer outcomes (as an example, see that co-authored by one of the event participants).

Why, for instance (and as canvassed in some earlier discussion), some households are willing (if they can, and perhaps through reductions in costs such as transport fares or second cars) to pay for walkability or proximity to particular schools or churches or to extended family and/or work. Meaning, for example, that retaining planning controls to achieve a “30 minute city” (as in the current Sydney plan) might be as important than loosening controls to simply increase house supply anywhere. And why, as shown in another revealing graph from one of the panel, neither “planning” nor the “market” are supplying the dwellings surveys suggest we want (with a preponderance on detached houses and density apartments, rather than the desired semi-detached dwellings).

And how, even if we can somehow reduce house prices by expanding city land boundaries, as suggested by some, there are always potential personal costs, as we now know only too well, if the result is simply more sedentary lifestyle commuter suburbs – costs relating to transport, time, health and wellbeing; and by extension also the public costs of delivering transport and services, from reductions in land available for food growing and environmental services, and from dealing with burgeoning chronic diseases. Considering these means the “sale price” line (re-conceptualised as a “whole-of-household” living expense) is going to be entirely different. Indeed, can that line ever be simply “structure cost” + “land cost”? Some of that cost is what we – individually and as a community – choose to pay for quality of life, and achieved through “zoning” (however defined).

“Zoning” is after all just some tools (amongst others) used to meet this larger city-living equation. As in any human endeavour they are applied with varying success. Research can assist. It also means planning instruments are constantly in flux, responding to changing wants and needs (the RBA study seems to portray them as more static, and indeed traditional research is more comfortable with particular points in time and space). And here again wickedness creeps in. This very fluidity, indeed willingness, to change planning “controls” facilitates another feature: speculation, the “hope factor”, particularly now in Australia where dwellings may no longer be just that but wealth-creation vehicles. And then of course there are contributory taxation regimes, and choices by developers themselves to “drip-feed” supply to maintain investment returns, and, and ……

The diagram is a useful picture. Sure, we need to “manage” the space in the middle to ensure the resultant price line is achievable (“affordable”). Detailed petri dish examinations are worthwhile. But it is also worth remembering the make-up of that space, and resultant policy, needs to be a lot more “multi” than a study like this can, alone, reveal. The Australian Public Service Commission in a report on how to deal with wicked problems in public decision-making suggests this need is an evolving art, but one which requires, at least:

- holistic, not partial thinking

- innovative and flexible approaches

- work across agency and discipline boundaries

- a tolerance of uncertainties, and

- an understanding of individual and social behaviour.

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.