By Dr Chris Martin, Dr Rebecca Reeve, Assoc Prof Ruth McCausland and Prof Eileen Baldry (UNSW), Pat Burton and Prof Rob White (UTas), and Prof Stuart Thomas (RMIT).

One of the classic metaphors for exiting prison is ‘going home’. However, more than half of people exiting Australian prisons either expect to be homeless or don’t know where they will be staying when they are released.

The connection between imprisonment and homelessness presents special risks for people with complex support needs: that is, those leaving prison who have a mental health condition and/or a cognitive disability. People with complex support needs are often excluded from community-based support and services because they are deemed ‘too difficult’, and so end up entangled in the criminal justice system.

Post-release housing assistance is a potentially powerful lever in arresting the imprisonment–homelessness cycle, and breaking down the disabling web of punishment and containment in which people with complex support needs are often caught.

In research published today by AHURI, we investigated the post-release pathways of people with complex support needs, and the difference made by housing assistance – in particular, public housing. We found:

- Imprisonment in Australia is growing and ex-prisoner housing need is growing; but at the same time, housing assistance capacity is declining.

- Without real options and resources, prisoner pre-release planning for accommodation is often last-minute. Insecure temporary accommodation is stressful, and diverts ex-prisoners and agencies from addressing other needs, undermining desistance from offending.

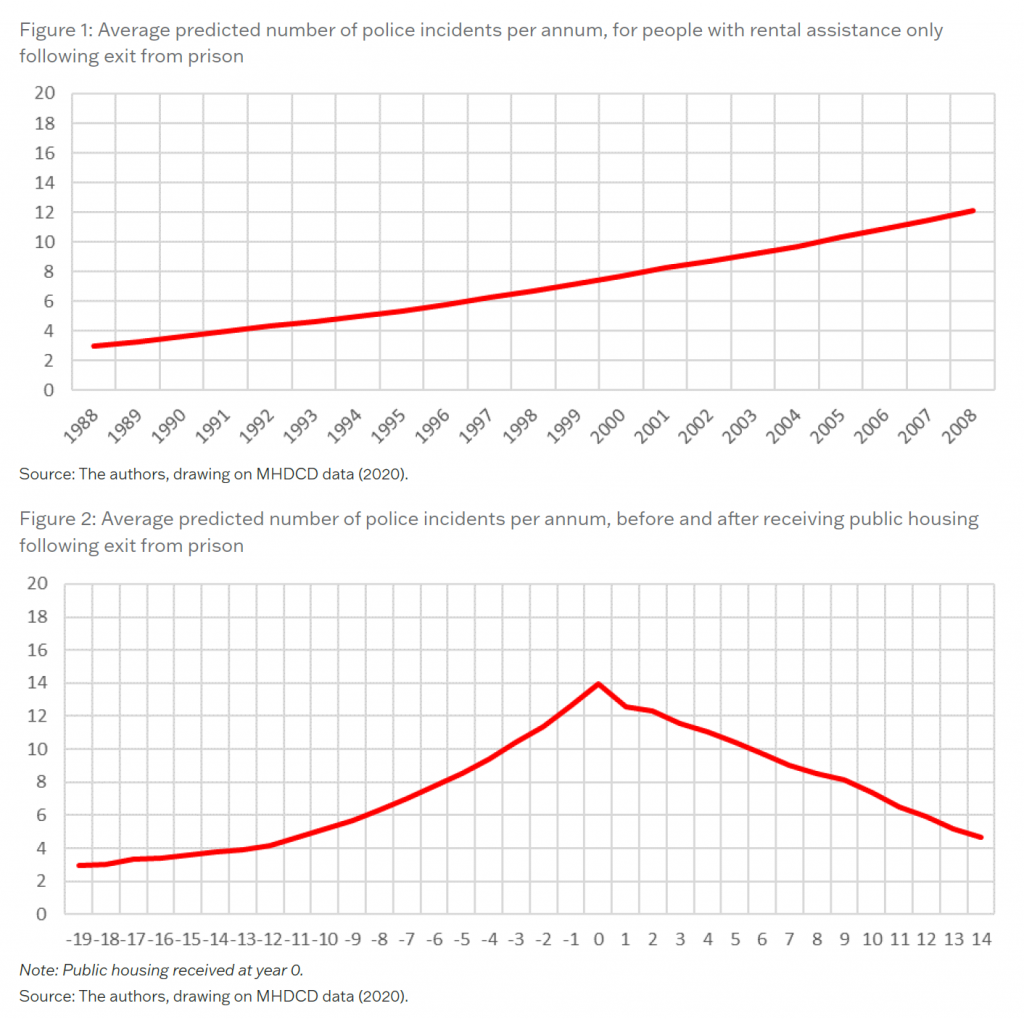

- Ex-prisoners with complex support needs who receive public housing have better criminal justice outcomes than comparable ex-prisoners who receive private rental assistance only: police incidents (down 8.9% per year), time in custody (down 11.2% per year), justice system costs per person (down $4,996 initially, then a further $2,040 per year), and other measures.

- In dollar terms, housing an ex-prisoner in a public housing tenancy generates, after five years, a net benefit of between $5,200 and $35,000, relative to the cost of providing them with assistance in private rental and/or through homelessness services.

Our findings about the effect of public housing on criminal justice outcomes and costs are the result of our analysis of linked administrative data from NSW government agencies about ex-prisoners with complex support needs. We compared two groups of ex-prisoners: one group of 623 ex-prisoners who received a public housing tenancy some time after their release from prison, and another group of 612 ex-prisoners who were eligible for public housing but received private rental assistance only. The charts below show average predicted police incidents per year for each group. For the ‘private rental assistance only’ group (figure 1), police incidents rose gradually over the period for which we have data. For the public housing group (figure 2), average predicted police incidents also rose until they received public housing (year 0 in the chart). Then police incidents turned down remarkably, and kept going down. Public housing flattens the curve.

The evidence strongly supports the need for much greater provision of social housing to people exiting prison, particularly for those with complex support needs.

Read the full report, the executive summary, and a policy evidence brief here, and the ABC’s report of the research here. This research is part of AHURI’s Inquiry into enhancing the coordination of housing supports for individuals leaving institutional settings.

No Comments so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.