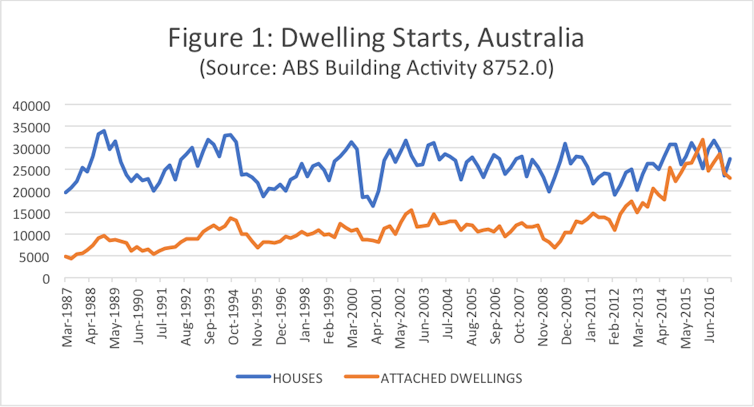

There is an ongoing debate about the best role for the planning system in addressing the shortage of affordable housing in Australia’s cities. At one end of the spectrum is the argument that its role in setting land value can be parlayed into mandating the inclusion of targeted affordable housing. At the other end is the argument that there is a need to simply remove planning constraints on supply, particularly on lower-cost housing options.

A good example of the latter has been the NSW State Environmental Planning Policy for affordable rental housing, or “the AHSEPP”. Introduced in 2009, the AHSEPP sought to remove barriers to, and even provide incentives to stimulate, the market delivery of housing options affordable for low-income households. The policy’s purpose as described in explanatory material highlights its role in addressing long waiting lists for social housing, among other worthy goals. Although broad in scope, the policy essentially relies on market delivery of secondary dwellings (granny flats) and boarding houses (called rooming houses in other jurisdictions).

But after nearly a decade of operation, there’s been no official position on what the policy is expected to deliver, or a review of its effectiveness. Given the importance the NSW government placed on affordable housing when it came into office in 2011, this might be considered surprising.

While some have sought to unpack the outcomes indirectly, Southern Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (SSROC) has worked with us to undertake the most comprehensive analysis of the AHSEPP to date, using primary planning data from its 11 member local council areas across central and southern Sydney.

More housing, but not more affordable

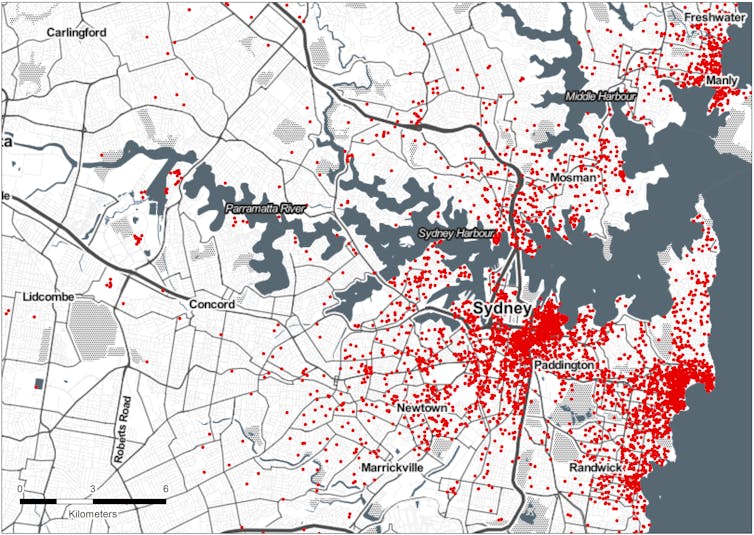

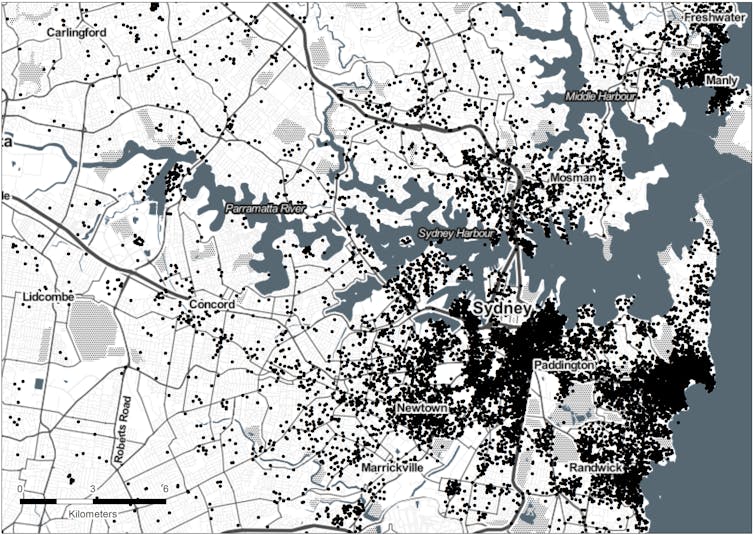

At one level, the AHSEPP appears to have delivered some significant results: over 8000 secondary dwellings and over 9000 boarding rooms have been approved since 2009 in this part of Sydney alone. This is a significant amount of development – as new dwellings, this would equate to about one in six of the total dwelling growth in this region between the 2006-2016 intercensal period.

But we found both secondary dwellings and boarding rooms were not markedly more affordable than what is already on the market in southern Sydney. This means that, if the private rental sector has not previously met the needs of some cohorts – as evidenced by the waiting lists for social housing – then the injection of supply through the AHSEPP does not appear to offer a remedy for this market failure. As such, and despite the extent to which the incentives were taken up by developers, it is difficult to claim success in its core objective of stimulating housing affordable for low-income households.

Equally concerning, we found evidence that very few of secondary dwellings were reaching the “formal” rental market, with only one quarter matched to rental tenancies. It appears that the provisions were taken up largely to accommodate informal expansion of the main household – actually fulfilling the true definition of “granny flat”! Similarly, the vast majority of boarding rooms were not rental housing available to everyone. It was clear from the geography, project description and proponent that these provisions were largely being taken up for student housing. A formal student housing option is a better outcome than the more informal ways demand has previously been met. However these new dwellings are hardly “affordable”, with rooms renting for over $400 a week.

So it seems that neither set of provisions were meeting the intentions of the policy: to deliver affordable rental dwellings and take the pressure off social housing wait lists. This highlights how difficult it is for planning incentives and regulatory dismantling to overcome this kind of market failure – that is, to make housing for people on low incomes profitable enough for private investors to deliver it.

Unplanned and uncounted

More broadly, the case of the AHSEPP raises other issues about how effectively the strategic planning accounts for this type of housing supply. Our analysis shows secondary dwellings are overwhelmingly delivered in established suburbs. Yet these areas have been conspicuously ignored as places for new housing by recent strategic planning policies.

This raises questions about the extent to which the population growth here is accompanied by a reciprocal growth in services and infrastructure. The absence of strategic planning for growth in existing suburbs has also established community expectations for little change here, meaning new developments (however merited) are met with strong opposition.

The injection of boarding rooms into areas already over-represented by both smaller dwellings and rental dwellings is also problematic. It suggests the policy is undercutting the objective of other government regulations attempting to deliver diversity in urban renewal contexts, where the challenge is supplying family-friendly housing options to build long-term community stability, not just student dorms.

So what use is planning deregulation?

The most specific conclusion that can be drawn is that this laissez faire approach to planning regulation, in the hope of overcoming previous market failures, has not been successful under the AHSEPP. More broadly, though, it shows how this approach to planning deregulation undermines many of the fundamental benefits of good urban planning – ensuring that the location of future growth is appropriately directed; that diverse and growing populations are effectively provided for; and that local context is considered and communities provided some certainty around anticipated change.