By Susan Thompson, City Futures Research Centre. This article originally appeared in New Planner – the journal of the New South Wales planning profession – published by the Planning Institute of Australia. For more information, please visit: www.planning.org.au/news/new-planner-nsw

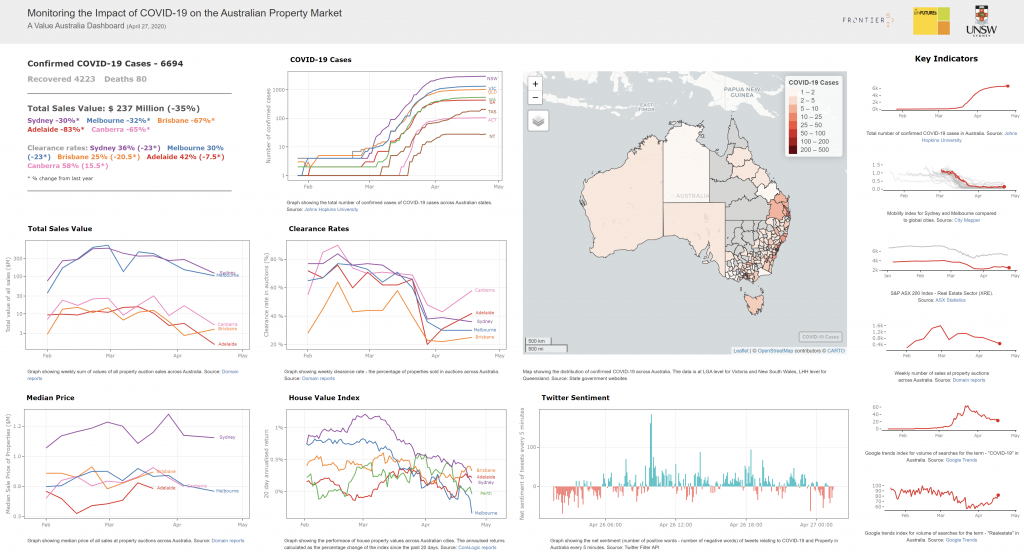

2020 had barely begun and Australia was in the midst of the worst bushfire season in living memory. Searing heat across the nation resulted in the tragic loss of human life, livestock, native animals and properties – homes, businesses, farms and bushland. Not only devastating for the directly affected communities and the Australian economy at large, but a wake-up call about the impacts of climate change on our health. And just as the fires were extinguished, another health crisis emerged.

The Coronavirus has engulfed the globe in an unprecedented challenge to our collective wellbeing, as well as our very way of life. At this time there might be some critics declaring that communicable diseases have caught advocates for healthy built environments unawares and scrambling for relevance. However, the current situation does not diminish in any way our need to pursue healthy built environments – in fact, what we are facing merely reinforces the importance of a health supportive environment for everyone. Indeed, for planners the present focus on human health is a reminder of the very origins of our profession and one of its central pillars – to improve health and wellbeing.

The principles of healthy built environments remain core to our health and wellbeing, as do the ways we create health supportive environments to make it easy to be physically active, socially connected, and to have access to fresh, nutritious foods. These are the most important behaviours that we can undertake each day to keep healthy and well. Not only do these actions reduce the major risk factors for chronic disease (obesity, lack of physical activity and social isolation), they assist in strengthening immunity. A recent post in ‘The Conversation’ highlighted the importance of being active in relation to supporting a resilient immune system.

A Focus on Local Space and Place

In an effort to halt the spread of the highly contagious COVID-19 virus, governments across the world have restricted the movement of people around towns, cities and regions, as well as between countries. Most of the population is spending considerable time confined to their local area – including homes and neighbourhoods. The result is that these spaces have never been more important and quite possibly, never better appreciated. This presents an unparalleled opportunity for those of us who plan, deliver and maintain local environments.

Most importantly, community engagement with the immediate and easily accessible neighbourhood reinforces the critical role that planning plays in delivering quality local environments. In NSW, the process of preparing Local Strategic Planning Statements (LSPS) underpins this function. In setting out the purpose of these visionary Statements, the Government’s ‘Guideline for Councils’ emphasises the local realm in relation to land use, identity, character, community values and responsiveness to change.

Ann Forsyth, Professor in Urban Planning and Design at Harvard University, recently reflected on the impact of COVID-19 on urban life and the part that planning needs to play in a pandemic. Much of her discussion focuses on the vital role of local environments in supporting working and studying at home, exercising nearby and shopping in the neighbourhood. Nevertheless, this comes with associated challenges, especially for those experiencing economic stress. Job losses will no doubt undermine security of tenure, which in turn poses a raft of threats to both physical and mental health. Secure, well maintained and appropriate housing is fundamental to good health and will be an ongoing challenge as we navigate life post COVID-19.

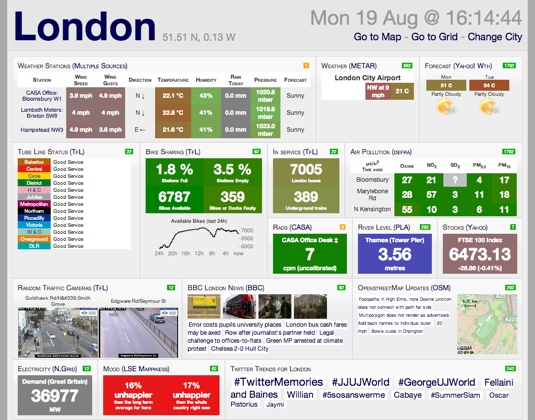

In an Australian urban context, Dr Sarah Barns, ‘city thinker and media innovator’ talks about the changes in urban rhythm (such as quiet streets, low traffic volumes, reduced commutes) as a result of COVID-19. She asks what might this mean for the future of urban spaces and places? Will planning and design need to shift its approach to urban density? Will the contribution that cities make to the modern economy be unravelled? Urbanist and cultural theorist, Professor Richard Florida thinks not. He acknowledges that cities and density pose vulnerabilities for highly contagious diseases, but they also hold the necessary infrastructure to fight the contagion. Throughout history cities have nurtured cultural innovation and improvements in health. Today, existing spatial and socio-economic inequalities are exacerbated by the pandemic – not as a result – and we should caution against a knee-jerk rejection of the urban.

Reflecting on the implications of the pandemic for planning, Mike Day, director of planning and design firm RobertsDay, notes that ‘the most resilient communities are walkable neighbourhoods’. Mike sums up the future possibilities in a way that reinforces core principles of health supportive built environments: the creation of ‘local, compact, pedestrian-friendly and connected’ places. Moving cars off the roads to give people more space to physically distance as they keep active by walking and cycling is also a critical topic of discussion and advocacy – during and after the pandemic.

A Focus on Local Social Connection

Local places and spaces are where we socially connect with each other. Feelings of belonging and attachment are central to human health and wellbeing. It is unfortunate that the term ‘social distancing’ has been widely adopted during the COVID-19 outbreak. A more apt descriptor is ‘physical distancing’ – the requirement to keep apart from each other in space. While this is necessary to reduce the risk of passing on the virus, we desperately need to be socially close. This is true for everyone, but especially so for vulnerable groups including older people, single person households, those with disabilities and families with young children. The impact of the pandemic response has unleashed creative ways of socially connecting while physically distancing – driveway dinners and teddy bear hunts! Showing kindness to each other as we share our anxiety in the face of the unknown has never been more important.

A Focus on Local Environments

The ways in which we can keep healthy and well during the pandemic provides a timely reminder of the critical importance of the environment – not just for humans, but for all life. Nothing has changed here – the crises of 2020 (both the bushfires and COVID-19) have merely reinforced the need for planners to protect the environment and foster social equity.

The provision of green space is one part of the environmental protection picture. Planners fully understand that easy access to quality parks is essential for good mental and physical health. As urban communities have navigated daily restrictions, they have benefited from the presence of swathes of green space that have escaped development. These areas offer much needed respite for everyone, especially apartment dwellers. The NSW Premier’s Priorities afford planners further opportunities to prioritise the provision and enhancement of green open space and the planting of trees. Plentiful green space and extensive tree canopy have never been more important.

A Final Note

While the different challenges facing all of us as we move through 2020 are extensive, they present a raft of positive opportunities for planning. This is especially so for those working at the local level – setting strategic visions and then delivering the resultant physical, social and environmental outcomes. Let’s use the renewed interest in local environments and culture to engage communities in the planning of their neighbourhoods in new and creative ways – now and into the post COVID-19 future.