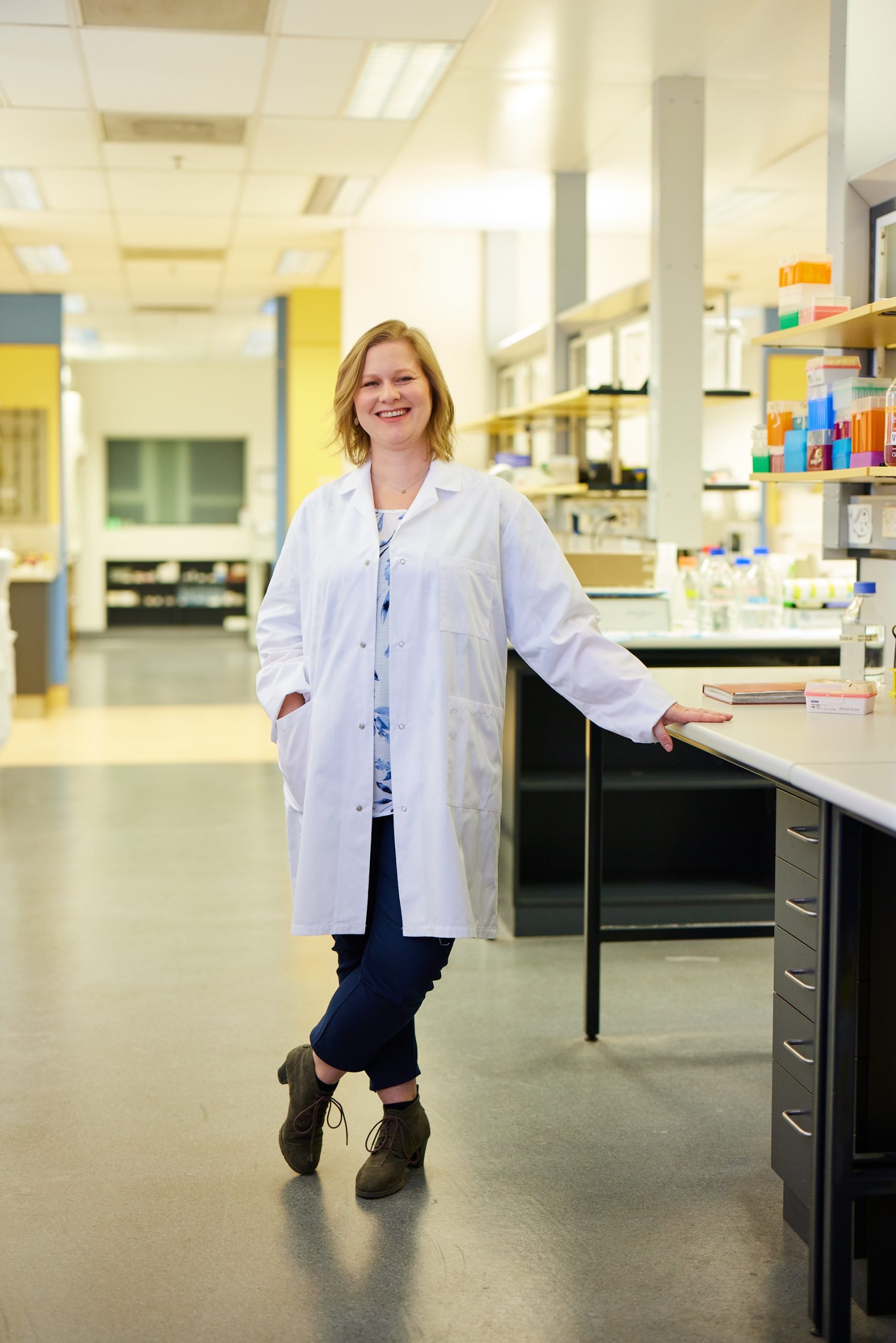

Meet Michaela Yuen

Female scholars pointed out family and domestic responsibilities as major sources of work-life conflict. Women in their early and mid-career levels are more likely to perceive work-life balance as a struggle between family and work commitments. In this article, Dr Michaela Yuen, a UNSW Women and Maths Champion, shares her career journey as an early career researcher and maintaining a commitment to her family.

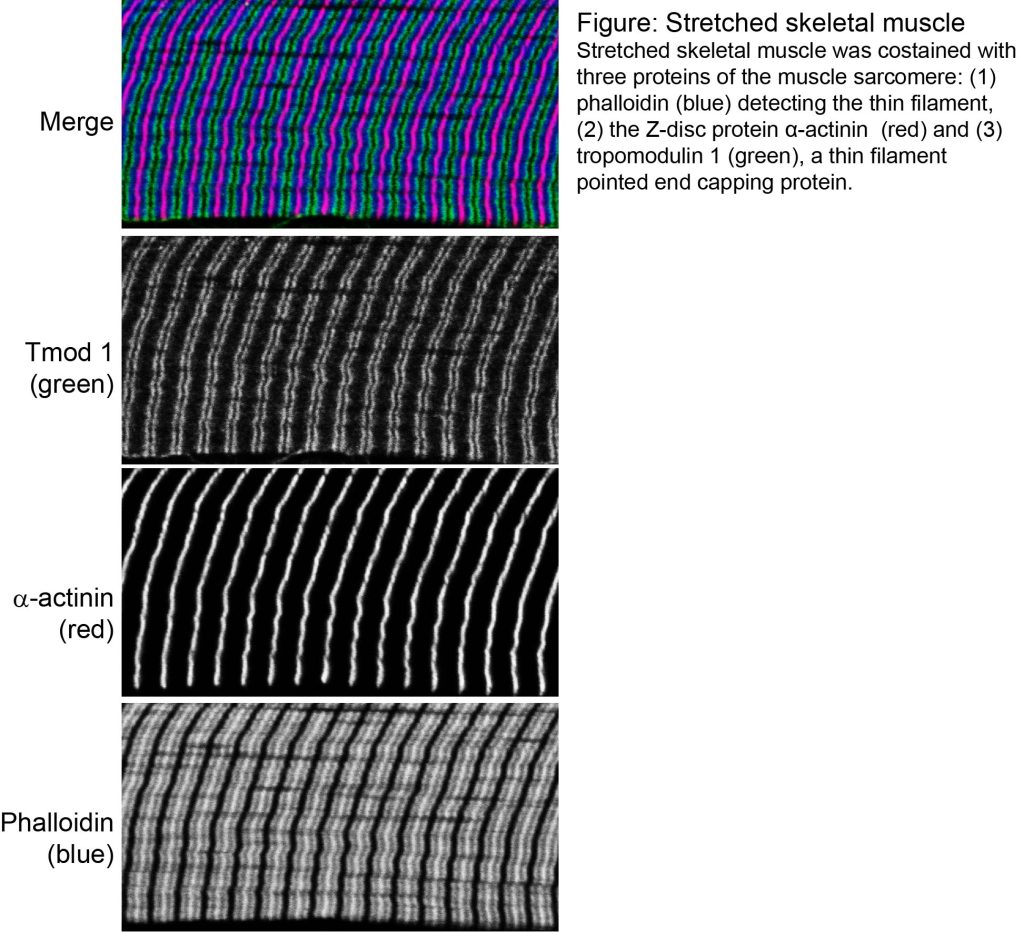

Michaela “Michi” Yuen is an Early Career Researcher (ECR) in the School of Biotechnology & Biomolecular Sciences at UNSW. Michi is a biomedical researcher passionate about understanding genetic neuromuscular disorders, particularly disorders affecting the muscle contractile apparatus. Michi has always been fascinated by the biomechanics and biophysics of skeletal muscles and how the structure of muscle tissue relates to its function in health and disease. The fact that her work has a real-world impact has been an especially important driving force and a constant motivator: Michi’s work on inherited neuromuscular disorders informs the clinical care of affected individuals by providing a genetic diagnosis and contributing to understanding the molecular mechanism of disease. Her work constitutes the critical first step in preparation for the development of targeted therapies, which are currently completely lacking.

Michi’s Journey towards Being a Biomedical Researcher

Michi obtained her undergraduate degree in biomedicine and biotechnology at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria. She first travelled to Australia as part of a summer studentship at the Institute for Neuroscience and Muscle Research, Kids Research, and the Children’s Hospital at Westmead with Prof. Kathryn North, an accomplished clinician-researcher in the neuromuscular field. She had a wonderful experience during the summer program and thus decided to return to complete a second research project as part of her Biomedicine and Biotechnology master’s degree and eventually enrolled in a PhD program at the University of Sydney within the same group.

After she completed her PhD, she received a prestigious CJ Martin National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) early career research fellowship. This fellowship provided salary support for four years of post-doctoral training, two years overseas at the Department of Physiology, University Medical Centers (Amsterdam, The Netherlands), followed by two years at the Kids Neuroscience Center, Children’s Hospital at Westmead, with her current mentor, Prof. Sandra Cooper. This ECR fellowship allowed Michi to study the genetic basis and molecular mechanisms of disease in a variety of skeletal muscular disorders. Her work involved biomechanical assessments of muscle contractile function, the analysis of patients’ DNA, RNA, and muscle samples, as well as establishing and assessing cell culture models of neuromuscular disease.

Building a Strong Collaborative Environment as a Researcher

Michi pointed out that, for her, one of the best parts of working on rare muscle disorders is that researchers in this field support a positive, friendly, and collaborative environment where the well-being of the patient is front and centre. Through her PhD and Postdoctoral work, Michi has formed strong connections with several leaders in her field. These professional relationships provide an avenue of support for Michi to build her confidence as an early career researcher. They offer a greater and more impactful reach of her work to the research community and the general public. A strong collaborative environment is critical for overcoming the big challenges that researchers, such as Michi, face when studying rare genetic conditions.

Since every patient is unique, every genetic muscle disorder is also incredibly unique. The work Michi does is targeted towards each patient, and most laboratory tests she performs are specific to the variant found in the patient’s genome. However, while each genetic condition is extremely rare, collectively, rare genetic disorders affect 1 in 50 individuals worldwide, meaning the work of Michi and her colleagues and collaborators is incredibly important. Since Michi studies genetic disorders caused by variants in many different genes, her research is very diverse, making her a bit of a “Jack of all trades, master of none”. While this is demanding, Michi enjoys this complex and dynamic research area, which allows her to dive into various methodologies and technologies.

The ultimate goal of Michi’s research is to diagnose, understand, and eventually develop a therapy specifically designed for each patient. Despite the challenging nature of working the extra mile for individual cases, she finds excitement in knowing that genetic therapies are becoming more available each day. She hopes that one day people working in this area will get better and faster at it and make a real difference in helping debilitated people participate easily in life—either to breathe, swallow, or stand.

Challenges as an Early Career Researcher

Being an ECR is tough. ECRs often have to juggle multiple projects, teaching, and other commitments. As a researcher, Michi is currently working on five different projects focusing on different genetic variants in individuals with neuromuscular conditions. Michi is working across several institutions, including UNSW, the Children’s Medical Research Institute, and the Children’s Hospital at Westmead. Her self-management strategy to handle the often overwhelming amount of work is to not always pick the ‘easy task’ but to focus on the task with the most impact, even if it is challenging. She uses this strategy not only to prioritize the research projects she is working on but also in other areas with conflicting priorities, such as undergraduate teaching and mentoring research students.

Managing Work-Life Balance

Outside of academic life, Michi is a mother of two. She starts her day by cooking breakfast, making lunch boxes, preparing her sons for school and doing school drop-offs. Having a supportive husband makes the juggle between home and work much easier, but it nonetheless feels impossible sometimes.

In addition to work and family routines, Michi loves to stay active and be connected with nature. Her favourite sport is horseback riding. For Michi, horseback riding is not only a great way to stay fit, but it also allows her to decompress after a stressful day at work. Since horses are very sensitive creatures, working with them makes Michi aware of any imbalances in her emotional state, forcing her to reflect and overcome negative feelings. She also enjoys gardening and being surrounded by nature. Michi is very passionate about understanding how everything in the ecosystem is connected. She feels strongly about teaching the next generation to understand the value of the natural world, treat it with respect, and protect it.

Don’t Give Up!

As a young mother working in STEM, she shared how challenging it is to get back on track following maternity leave. Her biggest challenges were to regain momentum in her research and to cope with the disruptions inherent in caring for young children. Michi expressed that young women working in STEM can find invaluable support to overcome these challenges by working within a well-set-up supportive research group and taking advantage of strong mentors and role models, as well as support programs offered by research institutions and universities. She also encouraged all women in STEM to keep pursuing their passion and not give up.

“Even if it’s sometimes a bit hard and there are a lot of roadblocks as a woman in science, if you’re sufficiently passionate about what you do, you’ll be able to overcome those. AND, MOST IMPORTANTLY, IT WILL BE WORTH IT!”

Get in touch with Michi through her social networks:

Twitter: @YuenMichaela

Instagram: @michi.yuen