By Vina Putra

Merryn is a Scientia PhD candidate in the School of Chemistry, UNSW. Her research focuses on analysing chemicals in the breath for the detection of lung diseases such as lung cancer. This could ultimately present a cheaper, non-invasive way to diagnose or screen lung cancer. Merryn is also passionate about translating her research to the clinics and into a business which led her and her team to win the Peter Farrell Cup in 2021 – UNSW’s prestigious entrepreneurship pitch competition for start-ups.

For Merryn, working on the fundamental science is just as important as research translation and science communication. Often, figuring out the mechanism in basic science can help present a solution, and bringing this solution to market requires a different approach and skillset that many scientists would benefit from learning. Working on a translational PhD project, Merryn finds it enjoyable to learn all the aspects of innovating and promoting not only the science, but also in establishing a business. In 2021, she and her team, Beagle, participated in the Peter Farrell Cup, a UNSW pitch competition for start-up companies, where they were awarded first prize in the higher degree research category. Their pitch brought Merryn and her team’s research on breath analysis a step closer to clinical reality.

Merryn’s PhD research focuses on the analysis of breath samples for disease diagnosis. Part of her research aims to identify the specific components in the breath that can be used as markers for diseases. Among the numerous types of chemicals in our breath, she focuses on aldehydes and ketones as they are known to be common biomarkers. Because these chemicals are present in small quantities in the breath (as low as parts per trillion!), Merryn uses Metal Organic Frameworks (MOFs) to enable detection. The MOFs serve as a net that can capture the chemicals in the breath and concentrate them so there is a sufficient amount to analyse.

In a typical week, Merryn would fill her days with teaching, demonstrating, marking, reading literature, analysing data, writing, and most importantly, working in the chemistry lab. Her experiments primarily involve running derivatisation reactions and mass spectrometry, which work hand-in-hand to improve detection. Mass spectrometry is an analytical technique that detects charged chemicals, known as ions, and the derivatisation reaction is used to put a positive charge onto the aldehyde and ketone biomarkers. By selectively placing the charge only on the analytes of interest, the mass spectrometry then detects only those charged chemicals, leaving all the noise and other chemicals aside. The mass readout from this can then tell which type of aldehyde and ketone are present in the sample. Depending on their concentration, some of these could be biomarkers for certain diseases. But sometimes, it is hard to tell because those chemicals may be just highly expressed with no association to any disease – what a challenge!

To really distinguish whether the aldehydes and ketones could serve as disease biomarkers, Merryn quantitatively analyses real breath samples using mass spectrometry and ion mobility spectrometry. She hopes to collaborate with clinicians and patients with lung cancer, as well as coal miners who are likely to develop lung diseases, and ultimately use their breath as references to establish a library of breath profiles between the healthy and the diseased. But the challenge does not end there – sometimes the breath profile of cancer patient does not match the profile of the cancer cells, which can happen as cancer may change the metabolic processes in the body, rather than produce chemicals directly. Merryn’s work contributes to the important task of identifying and characterising the specific chemical markers for lung diseases and testing the feasibility of using breath for diagnosis.

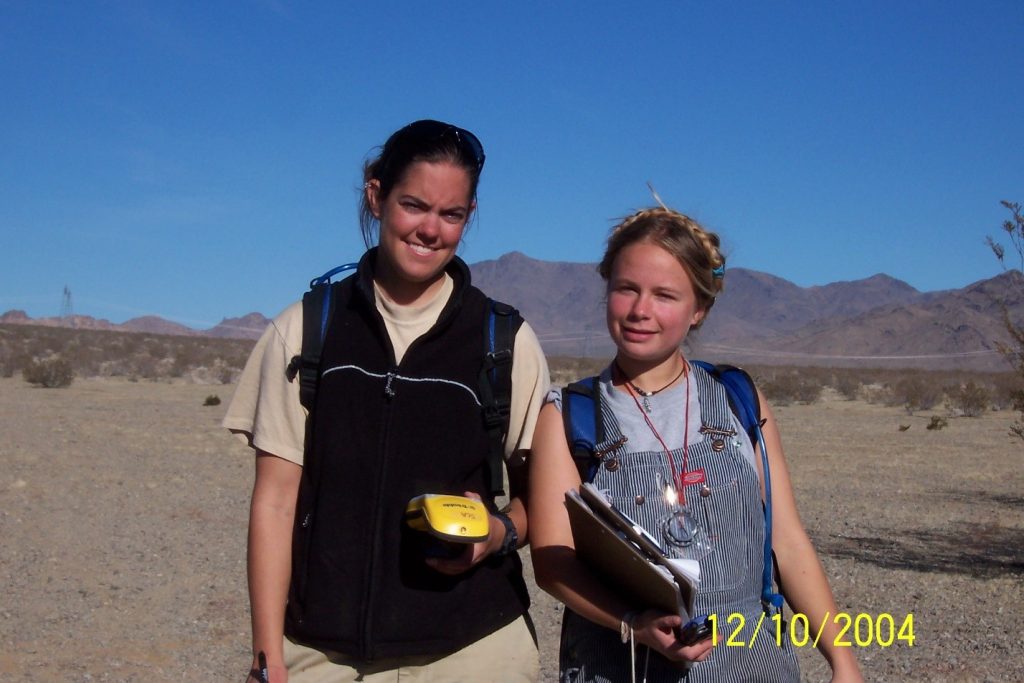

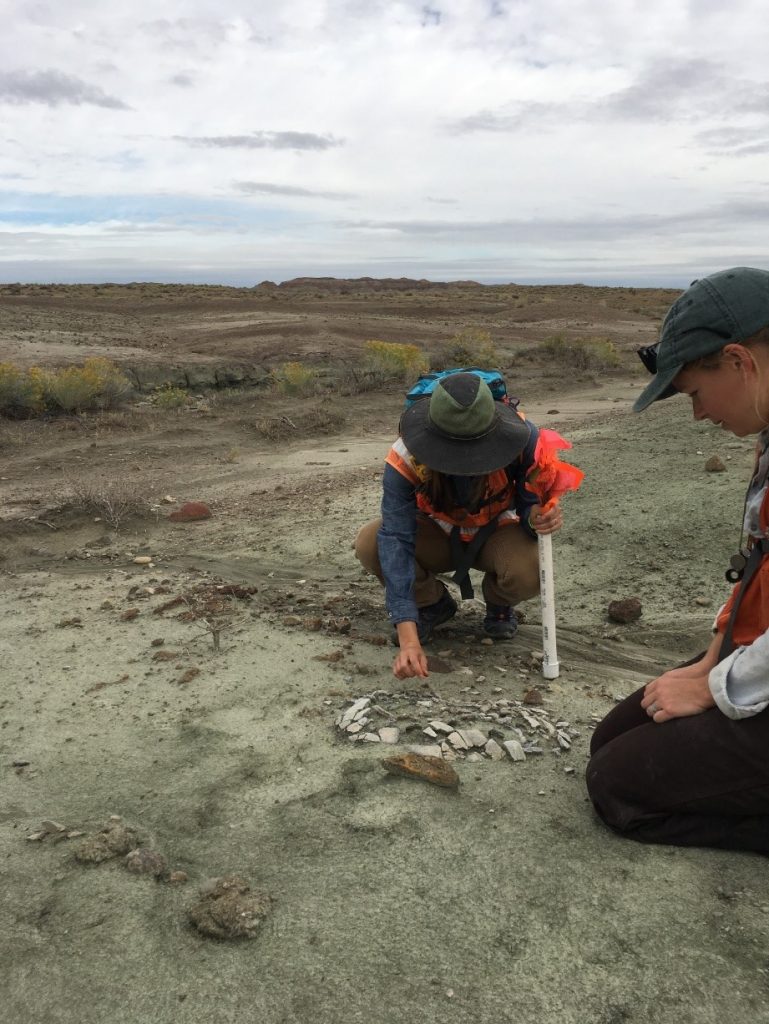

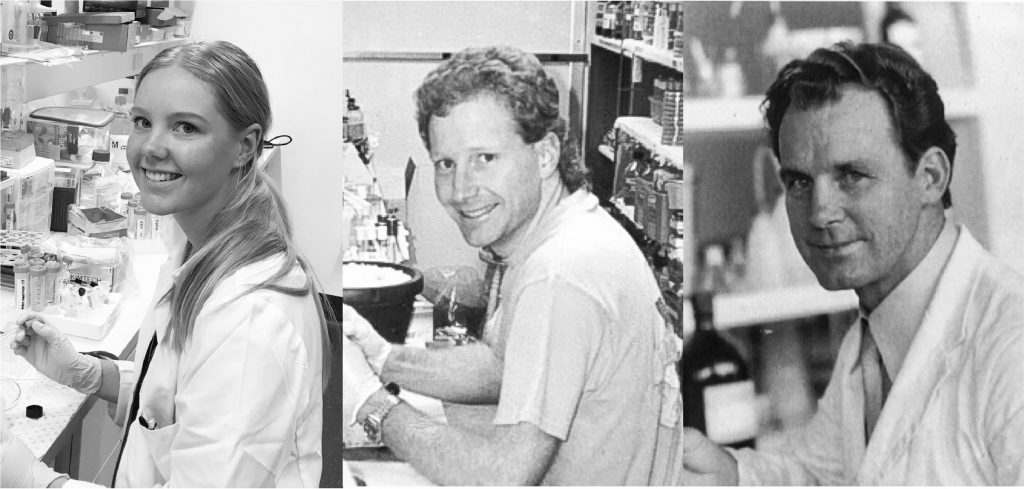

With the mentorship of her father and grandfather who both received their PhD in chemistry, Merryn always knew that science was an exciting and potential career path. Her journey started when she moved from Canberra to Sydney at the age of 10. In high school, she enjoyed the rigor and curiosity of maths and science, and how they enable a deeper understanding of our world. Her interest grew as she became amazed with spectroscopy – a tool that allows us to understand how atoms or molecules absorb and emit light, giving information about the structure and identity of that atom. It was her love for science that made her want to learn more.

Merryn received her B.S. in chemistry and physics in 2018 from UNSW and went to pursue research as an honours student in the school of chemistry. In her honour’s year, she found herself loving research and communicating research. She also enjoys teaching and demonstrating, and hence knew that she could be involved in all that a PhD program has to offer. Now 3 years into her PhD, she has been enjoying both the research and the opportunity for science communication, including being in the champions program. She is also a teaching fellow in the school of chemistry, and she works with the school’s education group to improve student learning and experience.

Along her journey in science, she has taken mentorship and inspiration not only from her amazing science teachers and supervisors, but also from her peers. Merryn added, “Being surrounded by other PhD fellows and learning from their achievements can be really powerful to figure out our own paths and aspirations – to learn how we can make an impact as scientists”. It is also possible to get inspiration from nature, as Merryn lives by the beach, she would go swimming or surfing in her spare time which helps boost her creativity.

As a champion, Merryn envisions a better future for women in STEM by cultivating an interest in science and maths from an early age, and to act as a mentor for these young women so they see STEM careers as potential pathways for themselves. “Often, young girls are being put off because people around them perpetuate the idea that science and maths are too hard”. Through the champions program Merryn aims to help promote young girls’ interest in science and maths – to change how they view the subjects from being hard to something rewarding and that serves as the key to solving many challenges in the world.

Follow Merryn on Twitter @merryn_baker