By Inna Osmolovsky

When we think of fieldwork, we usually think of the idyllic images of scientists engulfed by nature and breathtaking scenery. Fieldwork is indeed amazing, but it is also very challenging. Some challenges are unique for women and members of other marginalized communities. A recent fieldtrip sparked my interest in the experiences of women in the field. I had the honor to discuss these experiences with three women:

Maureen Thompson is a PhD candidate using FrogID data to better understand breeding ecology of frogs across Australia and how that data is structured: where, and why participants engage with the app and who they are.

Rosa Earle recently graduated with her honors in plant ecology, and who I had the honor to accompany to her first field work experience.

And, Charlotte Page, a second year Scientia PhD student, studying how global and local environmental stressors impact coral diseases and bleaching.

Although all three share a passion for nature, which sparked their interest in both biology and the field, each has a unique experience of fieldwork:

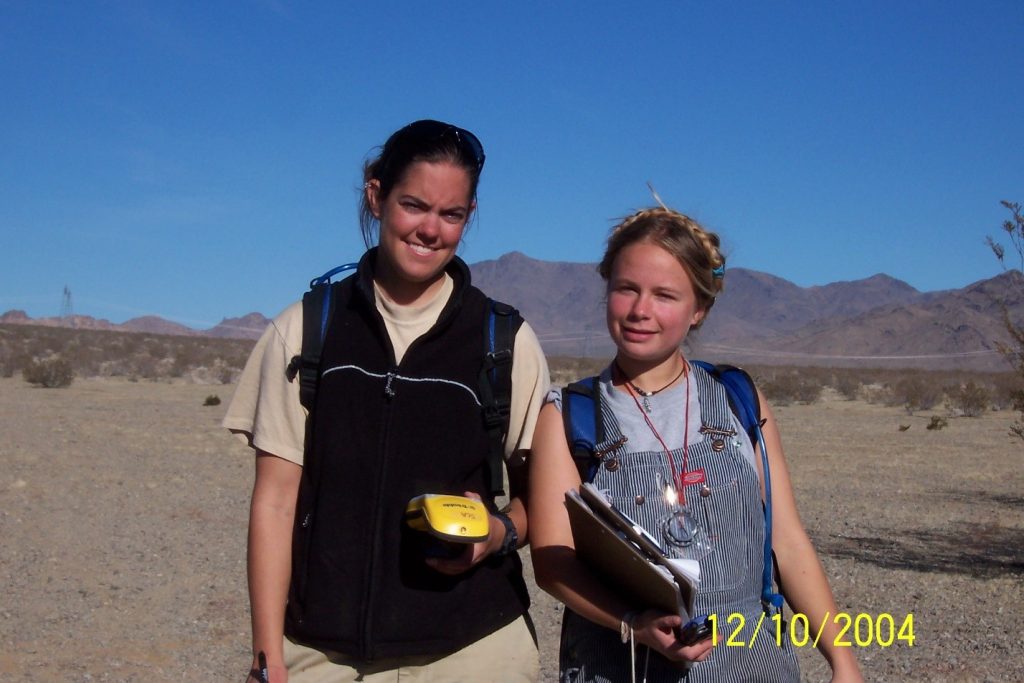

Maureen’s passion for the environment began after she graduated high-school, working as both a volunteer and an intern for nature conservation organizations. After graduating from college, she began to work as a field biologist for agencies and organizations in the US and across Central & South America. The types of projects would vary greatly: surveying anything from birds to mammals to reptiles, identifying plants and sampling soils. These experiences taught her to adapt quickly, to learn fast new information and techniques, to experience working both in groups and alone.

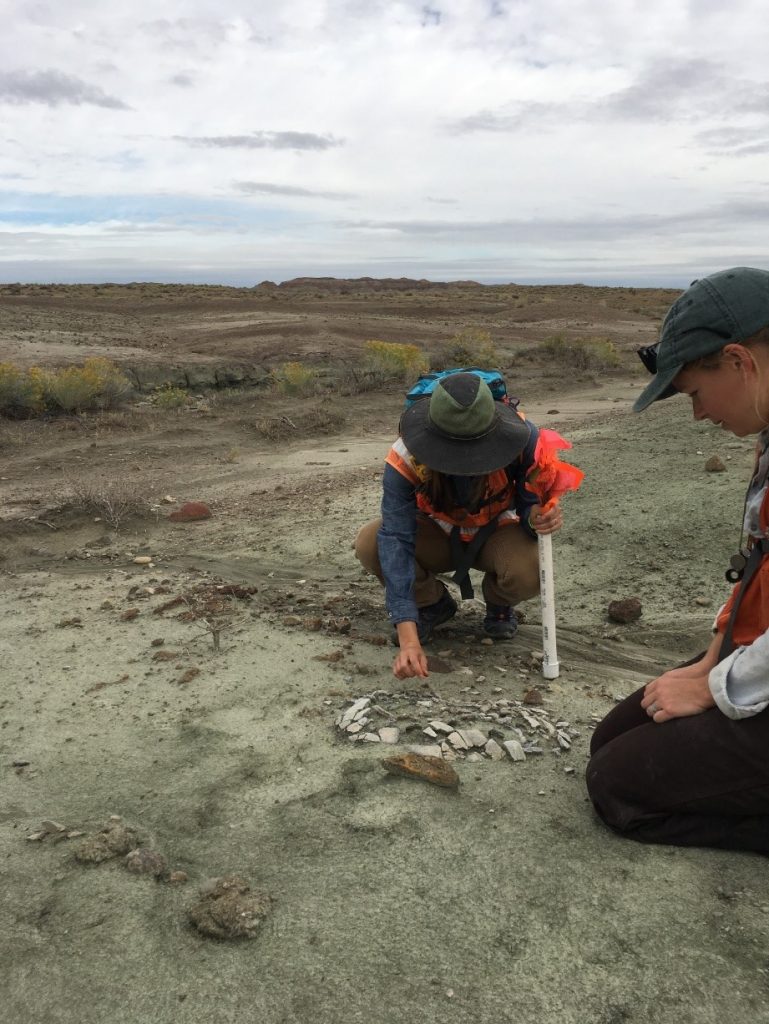

For Rosa, the love of nature from a young age inspired her to peruse a degree in ecology. One of her first experiences of fieldwork was on a vacation with her family near a field station. There she joined one of the PhD students for a frog survey. But, a lot of her experiences were affected by the global pandemic that began during the last year of her undergrad. All the planned field trips were canceled and most of the courses were taught online. COVID also affected her Honors project – she had to cancel a planned field experiment as Sydney went into lockdown, and to completely change her research. Thus, Rosa’s first official fieldtrip was in April 2022, when we went together to Mount Hotham. Since then she is working for an ecological consultancy agency, doing field-based surveys around Sydney.

Charlotte’s passion for marine science began when she started diving at school. She discovered an ocean teeming with life, beneath the calm surface. During her undergrad she got to spend a year in Queensland, and was lucky enough to spend time on Heron Island, the Southern Great Barrier Reef. “I thought, if this could be my job, that would be great”. It comes with no surprise, then, that Charlotte’s PhD is in coral reef science. She even went back to Heron Island as a PhD student, studying the physiological responses of corals to environmental stressors. But similarly to Rosa, Charlotte had to adapt and change her plans because of COVID – she was unable go to the field for a whole year. This made her appreciate the ability to be in the field even more.

Next, they told me their favorite experiences from the field:

“I love the unpredictability, it made me really resilient” says Maureen, which encapsulates a lot of what fieldwork is. Between finding messages in a bottle and rare moths, to random and weird encounters with people in secluded areas, fieldwork has it all. A particular experience she remembers fondly was when she studied the mating behavior of Cichlids (a type of fish) in a dry tropical forest. “It was like watching a soap opera”, she says, with the fish-moms and dads caring for their young. During this time she also encountered other animals coming to the pond where the survey was conducted. Her team, all women, were very supportive, creating a great working environment.

For Rosa, fieldwork is special because it offers the opportunity to learn about the environment in detail, while spending whole days outside. She reminds me of a funny story from our joint fieldtrip to Mount Hotham. The weather conditions were extreme, with 60 km/h wind speed and Icey rain, we continued to work through sheer determination. We would do the field work in short stints and then go back to warm up in the car. We were sitting in the car on one of these breaks and started to feel warmer, but actually the AC was turned to just 14 degrees during the whole time, which was still warmer than the outside.

One of Charlotte’s favorite things about the field is the ability to experience how mechanisms described in books play out in real life. She also really enjoys being underwater, observing everything playing out in front of her, witnessing new and unique things that sometimes no one has ever described before. She also values the experience of working in a team, making great friends and potential collaborators. A part of Charlotte’s research is conducted on Norfolk Island, and she finds interactions with the residents very rewarding. In communicating her science to them, she in return discovers how much they care about the environment and how much local knowledge they have about their surrounding marine ecosystems.

Indeed fieldwork is amazing, but there are often surprising and unexpected elements that are usually not communicated to the public:

One thing Maureen noted, is that usually the primary investigator (PI) of the project, who conducts the research, isn’t even present in the field. The work is actually carried out by temporary surveyors.

For Rosa, the amount of preliminary planning for the fieldtrip was surprising: “There are so many different little things that you need to think about to make everything go well”. It is important to have a good supervisor to guide you through the preparation and the fieldwork.

For Charlotte, fieldwork is quite an intense experience. It includes isolation from the external world and working around the clock with no designated time off. There are also the constant presence of other people and the fact that things don’t normally go to plan.

And of course there are outright challenging experiences:

Maureen mentioned that work as a field biologist is usually temporary and involves a lot of travel, with almost no constancy and income security, which might be challenging. One recurring negative experience for her would often happen when she was the expert, leading a team of other surveyors. When a passerby would inquire about what the team was doing, they would often direct the questions to a male team member. Even after Maureen’s teammate would address her as the expert, the person would continue to disregard her and talk to the male teammate instead. “But the most difficult experience is when the ignorant person is in your team”, she adds. She would navigate such situations by relying on her work ethic and by being logical, non-confrontational and empathetic while communicating with her teammate.

For Charlotte, fieldwork presents mental challenges. In the field, you might not have complete control over what you are eating, or where you are sleeping. In addition, you working for long hours and being in a constant contact with other people. She emphasizes the need take care of yourself while in the field. For her it means to bring a favorite tea with her to the field, or to wake up an hour earlier for exercise and personal time. Another challenge is that a lot of things don’t go to plan in the field. She had to learn to adapt quickly and to not be as strict with her plans.

With the challenges in mind, how can we make fieldwork safer, more inclusive and diverse?

Maureen suggests that diverse teams could be a solution for making the field more accommodating. While working together, bonding over shared experiences and hardships, like getting a car out of the mud, people become more open to listening and to accepting teachable moments.

Rosa adds that showing diversity when discussing fieldwork, or even hiking and being in nature, is an important step towards equality.

Charlotte emphasizes that we shouldn’t assume the capabilities of another person because of their gender and background. By discussing the abilities and boundaries of each team-member before the trip, we can insure that people are assigned with tasks that they are able to do and feel comfortable doing. Moreover, it insures that people feel safe not only while working, but also during leisure time.

Lastly, some advice for aspiring field-scientists:

“Definitely do it”, says Maureen. Although this is not the traditional 9 to 5 job, it is an experience like no other. She adds that while interviewing for a field based position it is important to interview the manager of the project, in return. Often you are hiring them to be your roommate and even your emergency response person, while in the field. She also suggests going for jobs that don’t perfectly align with your career path. They might unlock new and unexpected opportunities in your future.

Charlotte suggests to plan and prepare for the field trip, but to know that things will definitely change. Thus, it is important to manage your and your supervisor’s expectations. She adds that communication is important when working in a team setting. Talking through things, asking questions and being honest about your feelings and struggles can be very helpful.

Rosa also encourages anybody who thinks of fieldwork to go for it. There is so much you can get out of the experience. She also mentions the importance of good field gear, as weather might become extreme.

Follow us on twitter: