By Hal Pawson and Vivienne Milligan. First published by The Fifth Estate.

The NSW government’s new 20-year housing strategy gives a broad nod to issues at play while offering few actionable solutions.

With a transition from stamp duty to land tax flagged in Treasurer Dominic Perrottet’s 2020 NSW budget it appeared that the state could be on the brink of major housing system reform. Compounding this impression, was this week’s release of the Government’s Housing 2041 strategy and 2021-22 Action Plan.

The state’s first ever long-sighted housing strategy (emulating Western Australia and the ACT) is a welcome recognition of housing as both a major continuing challenge and a core policy responsibility of state and territory governments.

In its scope and aspirations the document refreshingly recognises the range of agencies, powers and policy actions available to state governments to achieve a better functioning and fairer housing system. As well as mooting the stamp duty reform, for example, it contemplates amending planning guidelines to promote housing diversity and sustainability, stronger consumer protection and support for tenants, “maximising the impact of government-owned land to achieve the housing vision”, and “rejuvenating” social housing.

Despite acknowledging the urgency for significant policy change, the strongest underlying message from the Housing 2041 documents is the Government’s desire to buy more time.

Another positive inclusion is new governance and coordination arrangements – including an expert housing advisory panel and a housing strategy implementation unit. These could help to confront the policymaking challenge posed by housing as a many-faceted issue badly served by silo government.

These strengths apart, though, how convincing are the documents as a genuine strategy? Qualities fundamental to the credibility of any meaningful strategy include: analysis of the problems to be tackled, setting clear and measurable goals, identifying actions to achieve those goals, and a plan for mobilising resources to implement the specified actions.

Regrettably, few of those features appear in the Housing 2041 documents.

First, they include no precise analysis of current housing market conditions, nor any quantification of existing unmet housing needs and housing system performance challenges.

Second, detailed modelling of demographic forecasts, population structure and inter/intra-regional migration is absent. Such projections are essential in planning housing supply targets, and never more so following the disruption caused by the COVID 19 pandemic.

Third, lacking concrete analysis as its foundation, stated strategy goals are extremely high-level in nature. This is revealed by a motherhood vision for NSW to “have housing that supports security, comfort, independence and choice for all people at all stages of their lives” to be achieved via one-word “pillars”: supply, diversity, affordability and resilience.

Under these headlines, there is little or nothing in the way of definitive targets and progressive milestones that would be needed to calibrate outcomes on any of these fronts.

While there are numerous stated aspirations for “more” or “improved” levels of activity, these are empty pledges without specifying (a) more than what, (b) how much more, and (c) by when the increased or enhanced activity will be achieved.

Only if defined as such would it be possible to assess future policy impact. For example, what is the current level of affordable and social housing supply across the system against which improvements will be judged?

What proportion of such housing falls short of acceptable standards and how much will this cost to fix? What is the target for reducing social housing waiting lists? How many first home buyers will government aim to assist?

Similarly, there are few numbers for current or required government housing expenditure cited in the documents. Admittedly, these could instead be provided in annual state budgets. But as the November 2020 Budget disclosed, relatively little additional direct expenditure in this area is currently envisaged.

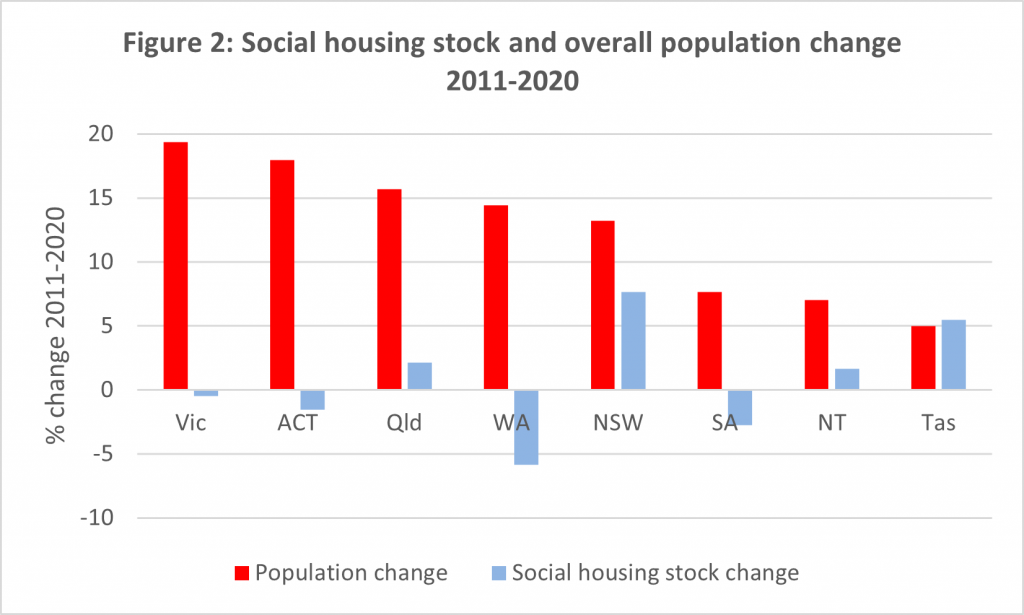

At a moment when a long overdue expansion of social and affordable housing could supercharge economic recovery, the best the government could come up with on this front was $400 million for additional new provision (most of the $900 million pledged in this area being for renovation rather than construction).

This sits in stark contrast to the Victorian government’s Big Housing Build – an all-time record investment of $5.4 billion over four years to achieve over 12,000 additional social and affordable housing dwellings – as announced late last year.

Not only is the NSW equivalent action pale by comparison, a systemic financial deficit of nearly $1 billion annually for the efficient and effective upkeep of existing social housing (as quantified in 2017 by the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal) remains unaddressed in the strategy.

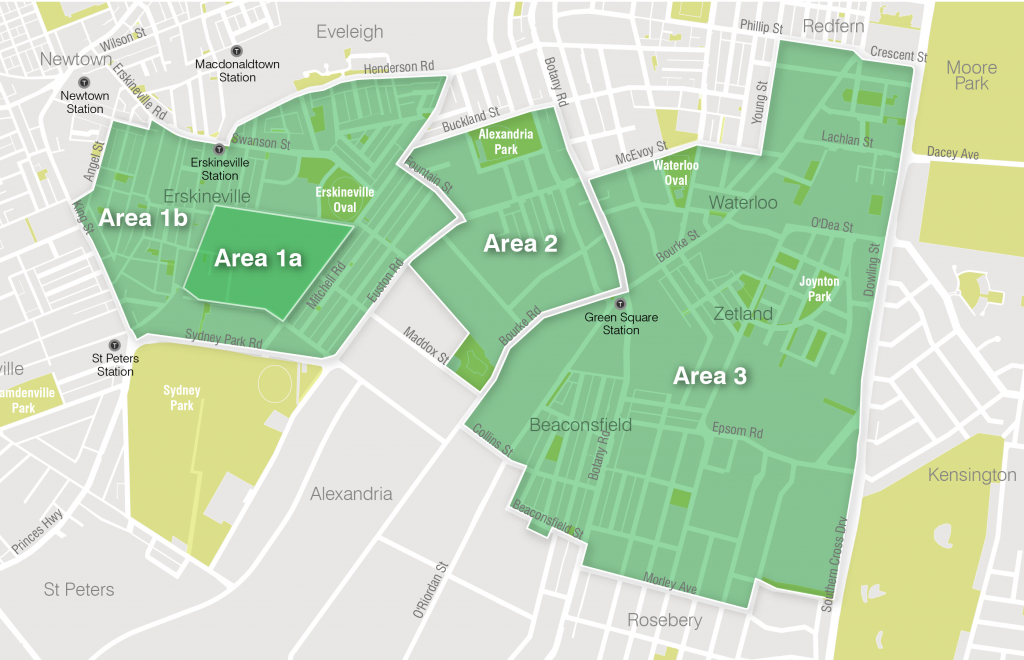

What is signalled instead is the NSW government’s ongoing enthusiasm to sell off public land and houses to help finance social rental modernisation and replacement. This, unfortunately, is a short-sighted approach, which will result in further loss of public assets and more widespread disruption and displacement for existing tenants in areas attractive to developers.

Despite acknowledging the urgency for significant policy change, the strongest underlying message from the Housing 2041 documents is the government’s desire to buy more time. Actions specified for the immediate future are predominantly policy reviews, new administrative processes, and evidence-building through data development and research; the kinds of activities often rightly dubbed “busy work“.

One timely exception is government support, previously announced, for a new build-to rent-product that offers potential to both improve consumer housing choices and the functioning of the housing system – respectively, by offering longer-term rentals and by diversifying developer options (and thereby reducing reliance on a build-to-sell model).

NSW government advocacy on this topic was also in evidence only last week in minister Stokes’s pointed call for complementary tax reforming action from the Commonwealth.

The promise of an effective long-term housing strategy for NSW has not been fulfilled… yet. For now, it appears that citizens will have to wait at least two more years (and until after the next election) to discover whether this state can develop a credible housing strategy. That would be one offering the scale and scope of reform necessary to reverse the renewed trend of worsening housing affordability; and one with meaningful and measurable goals as well as detailed plans and budgets to achieve them.