By Josephine Roper, PhD student, City Futures Research Centre.

Urban rivers can provide welcome open space, a cooling effect, scenic beauty and recreation opportunities, but can also be barriers to movement. Bridges are relatively expensive pieces of road infrastructure so are generally spaced out, rather than crossing a river at every possible point. But in areas where a road network was developed based on car traffic, the bridge spacing may be awkwardly far for people on foot.

As these areas densify, there are more opportunities to walk to a variety of local destinations, and more people looking to walk to them – but the natural barriers remain. Pedestrian (and bicycle) only bridges are more cost effective to build than car bridges, so extra pedestrian bridges have been introduced in some areas, but not all. I’ve written before about the spacing of bridges on the Cook’s River in Sydney. (https://walksydney.org/2020/04/08/wolli-creek-the-cooks-river-and-the-case-of-the-missing-bridges/ ) In this post, I will show in detail how adding 3 new bridges to the underserved region around Wolli Creek and Earlwood would provide people with improved walkable access to many more destinations, with potential benefits for property value and quality of life.

Walkability to local destinations

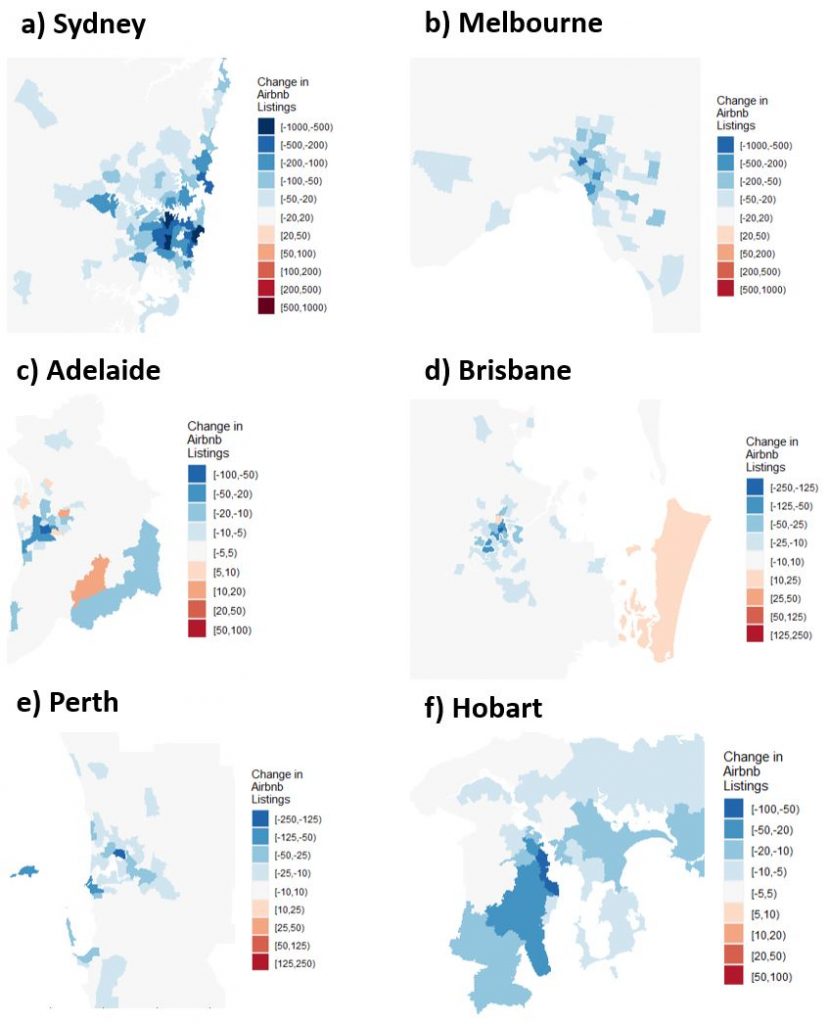

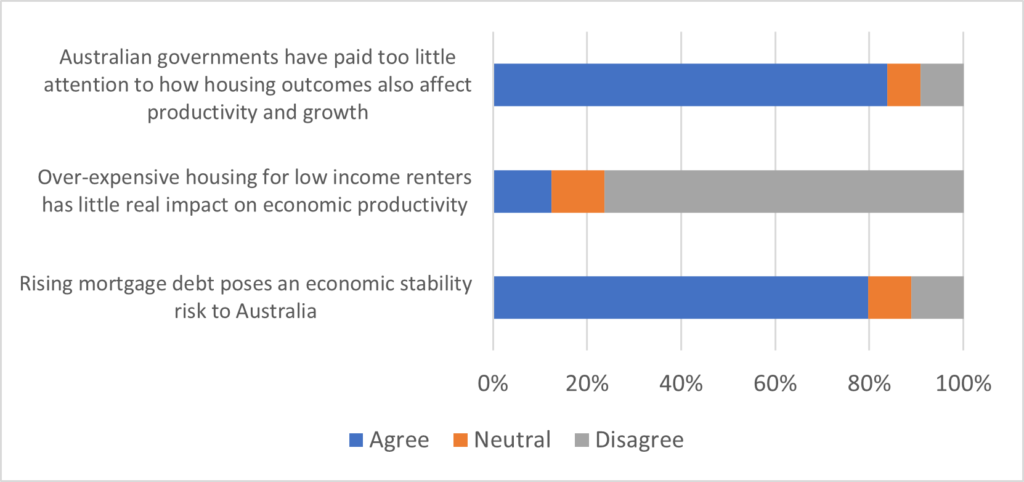

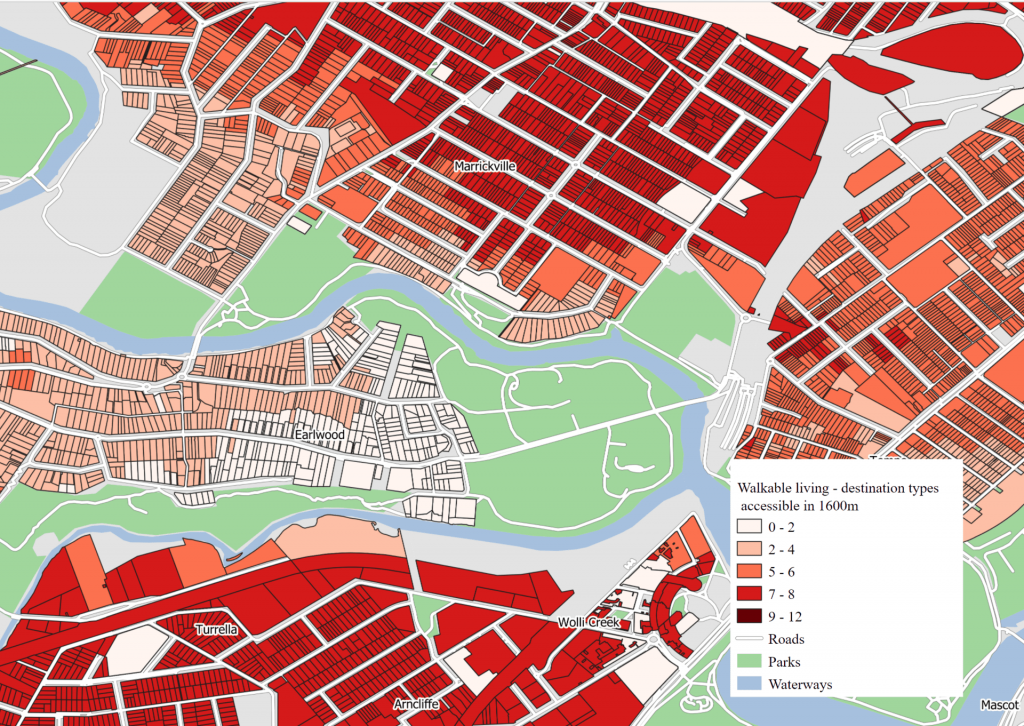

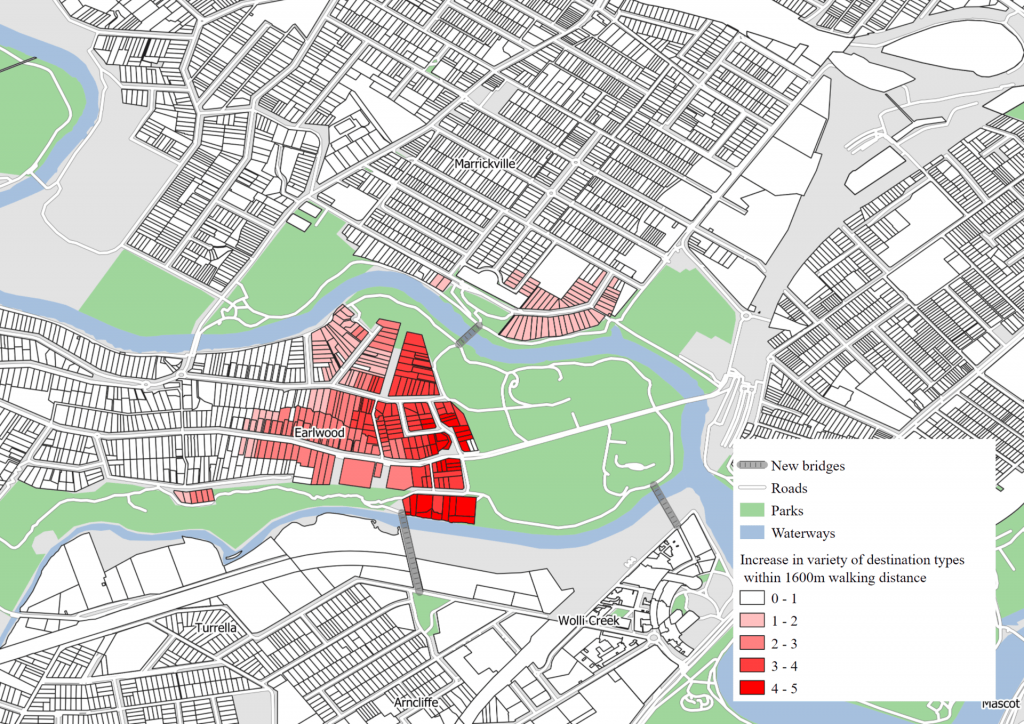

The map below shows properties coloured by a ‘walkable living’ score, a measure first designed by Mavoa et al (2018). Properties get one point out of 12 for every type of destination that can be accessed in a 1,600m walking distance from the property. The destination types are places that people commonly walk to if given the option, such as supermarkets, post offices, convenience stores and schools.

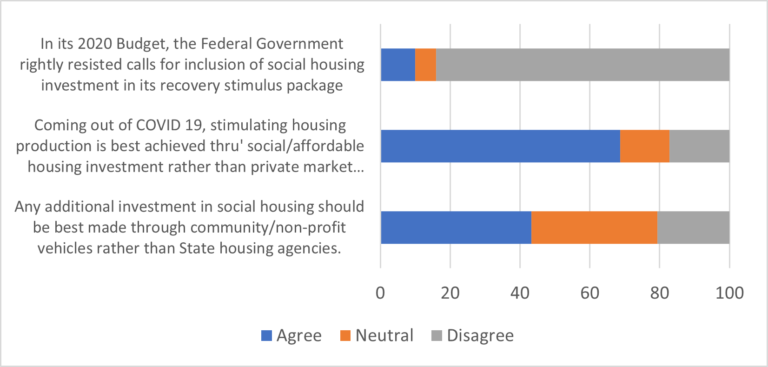

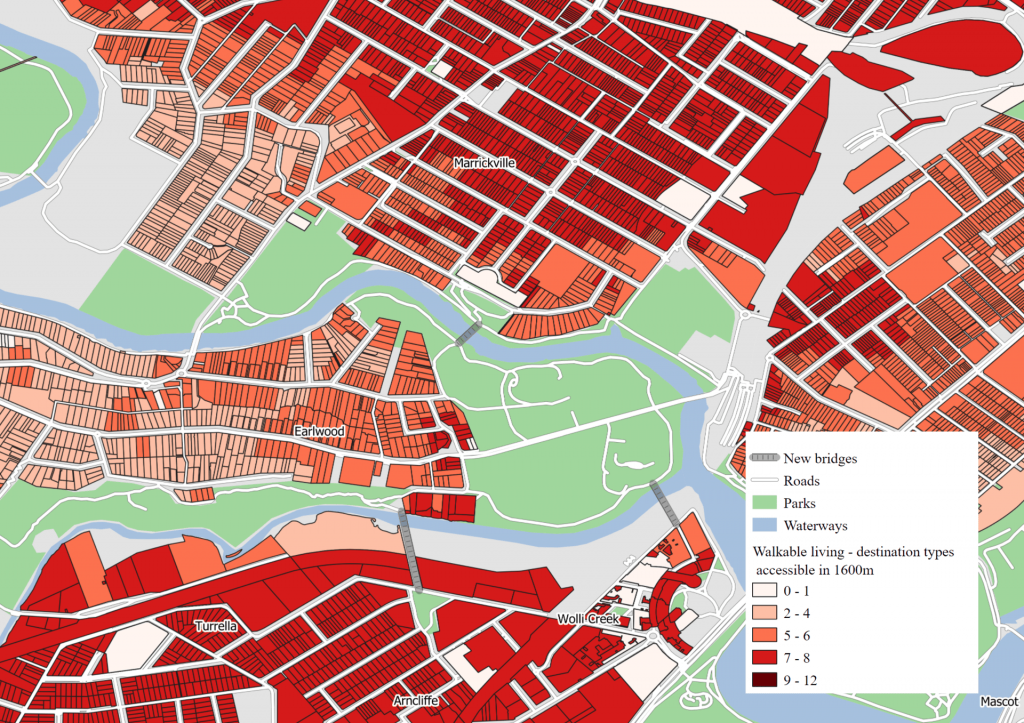

In the hypothetical scenario shown below, active transport connections were added in 3 key locations: 1) between Chisholm St, Wolli Creek and Waterworth Park, 2) between Lusty St, Wolli Creek and Tempe St/Waterworth Park, 3) between Pine Avenue, Earlwood and Warren Park, Marrickville. The total connections are up to 200 metres long as they extend to the nearest road or shared path, but the actual length of bridge required in each location would be less than 50 metres.

Comparing the two maps shows the benefits, primarily for properties in Earlwood, which show an increase of up to 5 types of destinations that are now walkable. A total of 1027 properties are positively affected.

| Increase in types of destinations accessible | Number of properties |

| 1 | 506 |

| 2 | 112 |

| 3 | 69 |

| 4 | 81 |

| 5 | 31 |

| 1 (within cycling distance) | 227 |

| Total | 1026 |

(Results for cycling are not shown on the map and are generally less as cyclists can already take longer detours to use the existing bridges, but some properties still benefited from an increased variety of destinations at a cycling distance of 5km).

Preliminary research into walkability and property value suggests that a gain of 1 point in this walkable living index increases property value ~1% for an average property in this area – around $10,000 a point. Combined, a possible $14 million value uplift for these properties.

An example of the change in accessible destinations for one property in Earlwood:

| Destination | Distance before bridges | Distance after bridges |

| Bank | >1600m | >1600m |

| Convenience store | 1355m | 1070m |

| Dentist | >1600m | 802m |

| Library | >1600m | 1561m |

| Post office | >1600m | 1449m |

| Community centre | >1600m | >1600m |

| Doctor | >1600m | >1600m |

| Public transport stop | 940m | 940m |

| Childcare | >1600m | >1600m |

| Pharmacy | >1600m | 1215m |

| Supermarket | >1600m | 1164m |

| Specialist food store | >1600m | >1600m |

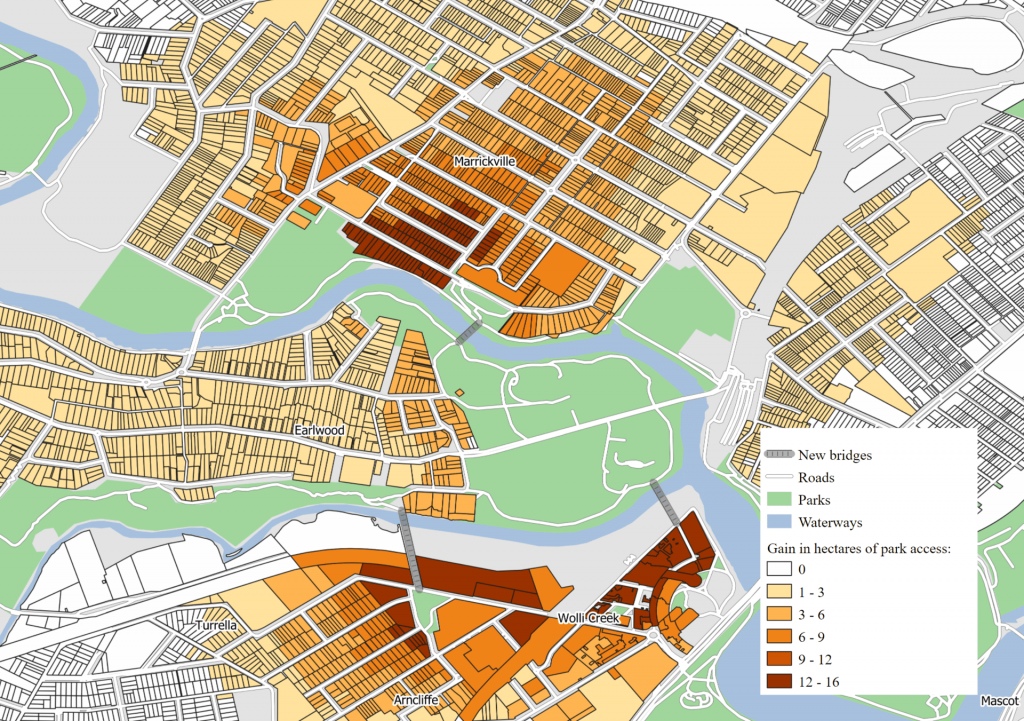

Park Access

I also analysed the change in hectares of parks accessible from each property. Approximately 15,000 people live within the map area shown and many benefit to some degree, but the largest change is for residents of the dense suburbs of Wolli Creek and Marrickville. The relative lack of open space for these residents has become apparent through the COVID-19 as more people have headed to the same set of parks to take exercise.

Conclusion

This analysis shows how network discontinuities that seem minor for car travel actually make a major difference to pedestrian accessibility. Results from ongoing work by the City Futures Research Centre suggest that pedestrian accessibility improvements translate to increases in property value, as well as quality of life, health and wellbeing.

Reference

Mavoa, Suzanne, Serryn Eagleson, Hannah M Badland, Lucy Gunn, Claire Boulange, Joshua Stewart, and Billie Giles-Corti. “Identifying Appropriate Land-Use Mix Measures for Use in a National Walkability Index.” Journal of Transport and Land Use 11, no. 1 (October 10, 2018). https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.2018.1132 .