Work on the Wolanski collection has underscored the vital role UNSW has played – and continues to play – in Australian cultural life. It has illustrated the value of bringing photographs, objects, oral history interviews and other production material together to gain a better understanding of what happened on stage. And it has raised heritage questions about the scattered information and artefacts relating to Sir Tyrone Guthrie’s production of King Oedipus at UNSW in 1970.

King Oedipus production photos, courtesy UNSW Archives

On 21 August 1970, Sir Tyrone Guthrie, the distinguished English theatre director, helped launch the Sir John Clancy Auditorium with the world premiere of John Lewin’s adaptation of the Sophocles tragedy, King Oedipus. The season at UNSW closed on 26 September before the production toured as a re-staged version in Canberra, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide until March 1971, with Dr Jean Wilhelm from the UNSW School of Drama in charge. A less theatrical official opening of the Clancy auditorium occurred a year later, on 23 August 1971

The University of New South Wales Drama Foundation, with financial support from the Australia Council, had arranged for Guthrie to come to Australia to direct the production by the Old Tote Theatre Company, which had been launched on the University of New South Wales campus in 1963. He had also been engaged to direct All’s Well That End’s Well for the Melbourne Theatre Company.

The 2-metre tall Sir Tyrone had visited Australia twice before. On the first occasion, in 1949 – the year the University of New South Wales was given statutory status as the New South Wales University of Technology – the invitation had come from the Australian Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, who had commissioned him to report on the establishment of an Australian national theatre. Guthrie had concluded then, as he concluded in 1970, that “Australia was not ready for a national theatre building.”

In fact, after a tour of the unfinished Sydney Opera House before the King Oedipus opening, he described the building as “an expensive knick knack”. It was “a mish-mash of buildings” and “quite inadequate.” Harking back to his 1949 conclusion, it was “putting the cart before the horse”.

He died the following year, in May 1971. Had he lived longer he may have reassessed his view on the value of buildings in stimulating growth of the performing arts industry in a far-flung country like Australia.

The local production

Guthrie had produced Oedipus several times before, beginning with his production for the Habimah Theatre, Tel-Aviv, in 1947. The Old Tote Theatre staging drew on Guthrie’s famous 1957 production of Oedipus Rex for the Festival Theatre, Stratford, Ontario.

The cast in Sydney included Ron Haddrick (Oedipus), Ruth Cracknell (Jocasta). James Condon (Creon) and Ronald Falk (as the soothsayer Teiresias) in the lead roles, as well as Jane Harders, John Hargreaves, Ivor Kants, John Wood, Shane Porteus and Pamela Stephenson. In early deliberations about the production, surprisingly Sir Robert Helpmann had been in the frame to perform the role of Jocasta. Richard Wherrett, who is not acknowledged in the program, had been engaged as an observer and diarist prior to his appointment as Associate Artistic Director of the Old Tote

For Ruth Cracknell the joy of working with Guthrie was one of the high points of her career. In an interview with Michelle Potter for the National Library in 1986, she recalled Guthrie’s insistence that it be performed with Australian accents.

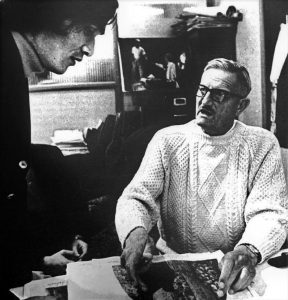

Sir Tyrone Guthrie discusses King Oedipus with designer Yoshi Tosa. Source: Wolanski Collection, UNSW

Ronald Falk, who played Teiresias, in an interview with Margaret Leask, also treasured the experience of working with him. “He listened all the time.” He was “very conscious of the sound of the thing.” He had a memorable way of giving direction. After Falk had attempted a challenging stage movement, he received the following suggestion from Guthrie: “Ronald: just a little less C major, please.” Hinting at the organic nature of works on stage, Falk felt the production never came into its own until it reached the Octagon Theatre in Perth the following February.

The set and costumes were designed by Yoshi Tosa, who in another oral history interview with Leask, described the work that had begun six months before the opening to produce 80 masks, 55 costumes, and platform shoes for the principals to elevate them in height and status.

The music for the production was composed by the late Roger Covell.

The reaction

There were mixed reviews.

HG Kippax, the Sydney Morning Herald critic, was disappointed but urged everyone to see it. “Sir Tyrone Guthrie’s visit has been eagerly awaited, and no theatre-lover no matter what I or anybody else says, should miss his production of King Oedipus at the Sir John Clancy Auditorium at the University of New South Wales”. It was a conception of “perhaps the greatest work of pessimism every written, staged with sustained grace and beauty.”

Yoshi Tosa’s settings and costumes were singled out. Robin Ingram, in The Sun, wrote that “so much awe that this production holds is in [Tosa’s] lavish masks and costumes.” Ursula O’Clonnor, in The Sydney Morning Herald the following year recalled: “the one thing that most people agreed on was that was visually stunning”.

Robin Ingram, in The Sun, described it as a “momentous production.” Katharine Brisbane in the Australian praised the standard of performance and mounting as “way in advance of the Old Tote Company’s work for some time.” However, The Daily Telegraph’s Barbara Hall remembered it as “a dream that did not come to life”. And Brian Hoad, in The Bulletin, was scathing. He saw it as a “tragedy transmuted into something more like vaudeville comedy”.

The auditorium was savaged as a theatre venue by almost everyone.

A fortnight before the opening, Guthrie had put the hall’s acoustics to the test in front of an audience of 900 school children, drama students and the singer and comedian Anna Russell, before declaring the acoustics “ain’t so bad as we afeared.” Kippax, however, blamed the acoustics for his disappointment, along with the inclusion of an interval, which he said destroyed the play’s long controlled movement of climax. Most participants and commentators agreed.

The choice of the theatre, however, had been Guthrie’s. Robert Quentin had offered him the 330-seat Parade Theatre nearby or the 999-seat Sir John Clancy Auditorium. After an unsuccessful search for other options, Guthrie chose the larger auditorium, despite its stage limitations and questionable acoustics, over the more limited seating capacity of the Parade.

There were indelible impressions.

Two high school teachers, OC Mortimer and BM Potter from Parramatta, who had brought with them a class of students, read Hoad’s damaging critique with disbelief. “It was a profound experience among a spellbound audience” and had “made out lives richer for seeing it.”

On the other hand, Deborah Jones, remembering years later her visit as a Year 12 student from Newcastle, could recall nothing other than being bored, except for the impact of the “elaborately stylised costumes and masks of Yoshi Tosa’s design.”

For another schoolboy, Tony Knight, later Head of Acting at NIDA, “it was massive, with all the characteristics of Guthrie’s particular ‘epic’ style. Everything was big – the masks, the costumes, the theatre space – everything.”

In his view, it was partly due to Guthrie that the respective state theatre companies and NIDA were established, and he had a major influence on John Bell and Anna Volska, who worked with Guthrie in the UK during the 1960s.

Lex Marinos “was among a squad of plague-riddled Thebes supernumeraries needed for a groaning, smoky opening scene. Most of them were NIDA students.” It was an experience that left its mark: “By the time I graduated, there was only one thing I aspired to – I wanted to be a jobbing actor.”

In part 2, we will look other UNSW connections and production records.

Selected sources

- Forsyth, James. Tyrone Guthrie: a Biography. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1976.

- Jones, Deborah. ‘Statements on stage: 50 years of Australian Theatre, dance and opera’ (The Australian, 16 May 2014)

- Knight, Tony. ‘Michael Billington’s The 101 Greatest Plays, #2 – Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex’ in All the Pleasures of the Garden [Website] https://allthepleasuresofthegarden.com/category/oedipus-rex/

- Kippax, HG. ‘Disappointing – but See Oedipus’ in A Leader of His Craft: Theatre Reviews of HG Kippax. Strawberry Hills: Currency House, 2004.

- Marinos. Lex. The Jobbing Actor: Rules of Engagement. Platform Papers no 53, November 2017. Strawberry Hills, NSW: Currency House.

- Oedipus Rex. Canadian Stratford Festival production by Sir Tyrone Guthrie, 1957. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TonLOAkc1OY. IMDB https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0050792/

- Wherrett, Richard. The Floor of Heaven: My Life in Theatre. Sydney: Hodder Headline, 2000.

Author

Paul Bentley is assisting the Performance Memories Project to improve the accessibility of the Wolanski collection in the UNSW Library. He saw the production in the Sir John Clancy Auditorium, looked after some of the masks and costumes from 1973 to 1997, and performed the role of Teiresias for the WEA Studio Theatre, Newcastle, in 1967.