By Hal Pawson; CFRC

With newly released evidence of slowing house price inflation in early 2022, it may be that Australia’s latest property boom is subsiding. Especially with higher interest rates expected within months that seems highly likely. But any plateau or even gentle decline will be starting from property values dramatically higher than before the pandemic.

By late 2021 the typical Australian house was 30% more expensive than in early 2019. That will have markedly raised the barrier faced by aspiring first home buyers, especially in terms of mortgage down-payments. After all, wages increased by only 6% over this period.

Far from triggering a property market crash, as widely expected, the 2020 COVID-19 recession turns out to have activated an extraordinary residential price surge. And, as highlighted in our new international comparative research, Australia is far from alone in this. The equivalent COVID-19 house price increases in New Zealand the United States have been even greater.

Sources: OECD and UK Office for National Statistics

In fact, during the pandemic to date, nominal house prices rose in all eight case study countries covered in our research – Australia, Canada, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, the UK and the US. In sharp contrast to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, none of these countries saw any significant nominal price decline episodes in 2020 or 2021.

What ‘saved’ the market?

Avoiding a pandemic-triggered housing market slump can be largely credited to the remarkable government measures to maintain incomes and shield economies, widely implemented during the first two years of COVID-19 both in Australia and internationally.

Extraordinary actions that directly safeguarded housing systems and tried to protect at-risk populations also helped to confound initial fears of crashing property values and surging homelessness. Activities of this kind – as seen in most of the countries covered in our research – included mortgage payment deferrals, rental eviction bans and emergency housing for homeless people.

What powered prices?

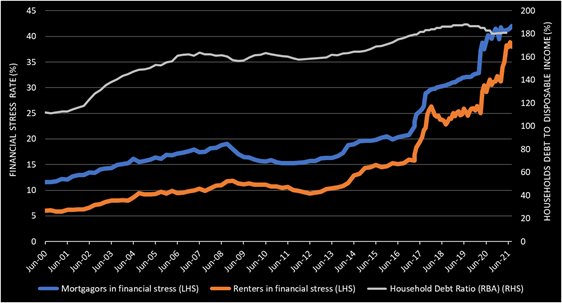

While measures like this seem to have effectively placed a floor under the market in 2020, other factors combined to touch off the price booms widely seen in 2021. Crucial to this have been the rock-bottom interest rates and quantitative easing measures that have formed key elements of central bank responses to the crisis around the world. While deemed essential to protect economic activity, these have also pumped vast liquidity into housing demand.

In Australia and the UK an additional factor was direct government-funded housing market stimulus – generous home purchase grants and stamp duty concessions initiated in 2020. With hindsight these look to have been a misdirected form of official pandemic response, since they only compounded market overheating.

In some countries pent-up household savings will also have contributed to price booms. Many better-off households, working from home through the pandemic, with unusually low expenditure and with housing wealth to cash-in, have been motivated to spend big on improving their housing position. At the same time, many others have been priced out as a result.

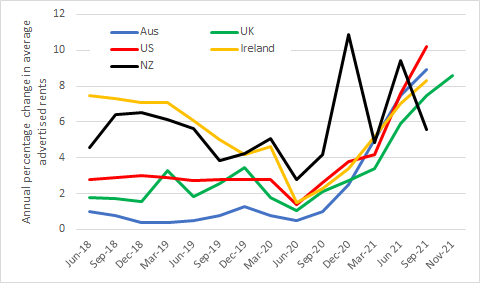

Spiking rental markets

For lower income households pandemic-triggered housing cost pressures have been more importantly intensified through the equally marked spike in rent inflation seen in Australia and in many other countries in 2021. Whereas some of the nations in our research had restricted rent increases in the early ‘income shock’ phase of the pandemic, almost all had lifted these limits when rents began rising, on shifts in demand.

By year end 2021, with the possible exception of Canada, national annual rent increases were topping 8% in all of the Anglosphere countries – a rate of increase generally far exceeding past decade norms. Rent inflation in Australia, the UK and the US was, by this time, running at rates unseen since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Sources: Multiple – see Figure 6.1 in published report for details.

Equally, there have been marked within-country variations in pandemic rental market impacts. In Australia, for example, Sydney and Melbourne rental demand in many inner areas was hard-hit by international border closure through most of 2020 and 2021, through the resulting absence of overseas students and foreign tourists. By year end 2021, capital city rents across Australia had barely recovered to their pre-pandemic values. Rental prices in non-metropolitan Australia, by contrast, were on average 18% higher than at the start of the crisis.

Higher rates of property price and rent inflation affecting non-metropolitan locations and houses (as opposed to apartments) have also been seen in other countries during the pandemic. These trends probably also reflect the residential ‘race for space’, a trend powered by the rapid rise of working from home. This has placed an increased premium on property size and also weakened spatial ties to city centre office locations, enabling many (generally more privileged) employees to contemplate out of town moves. As a result, pandemic-triggered damage to housing affordability is likely to be all the greater in the non-metropolitan settings attractive from this perspective.

Different stories in Germany and Spain

Importantly, much of the preceding account most directly describes pandemic-era experience in Australia and other Anglophone countries. The market impact has played out quite differently in some other high income nations. In Germany’s house sales market, for example, relatively robust pre-2020 price growth continued on a similar trajectory during the crisis to date. Spanish price growth, meanwhile, remained subdued.

Germany’s rental market likewise appears to have been relatively unaffected by the pandemic, with rent inflation generally continuing to moderate during 2020 and 2021. In Spain, meanwhile, rents continued to decline in nominal terms.

The German experience here probably reflects the country’s unusually stable and resilient economic and housing systems, a tradition of conservative mortgage lending, and a stronger social safety net. For Spain a key factor affecting the nation’s economy and housing market during COVID-19 will have been the heavy damage sustained by the dominant tourism industry.

Housing affordability impacts

Although in key respects contrary to predictions, the direct and indirect housing system impacts of COVID-19 have been profound. Not all of the novel housing market trends seen in 2020 and 2021 are likely to be sustained. But, as things stand two years after the pandemic was declared, consequently rising house prices and rents will have further intensified housing affordability stress in many nations. Specifically, in five of the six countries for which we have obtained national statistics, nominal rent increases exceeded wage increases in the two year period to late 2021.

Coinciding in many countries with energy price and tax rises, these developments will only compound the cost of living crises evoking calls for action to cushion these impacts – including through enhanced rental housing regulation and investment, and stepped-up social security payment rates.